Here is an interview I have done with artist Eric Banks. Eric is one of the artists in the show Three Painters at Duck Creek, which I curated for the Arts Center at Duck Creek. I enjoyed our conversation tremendously and I thank Eric for being a part of the fantastic show.

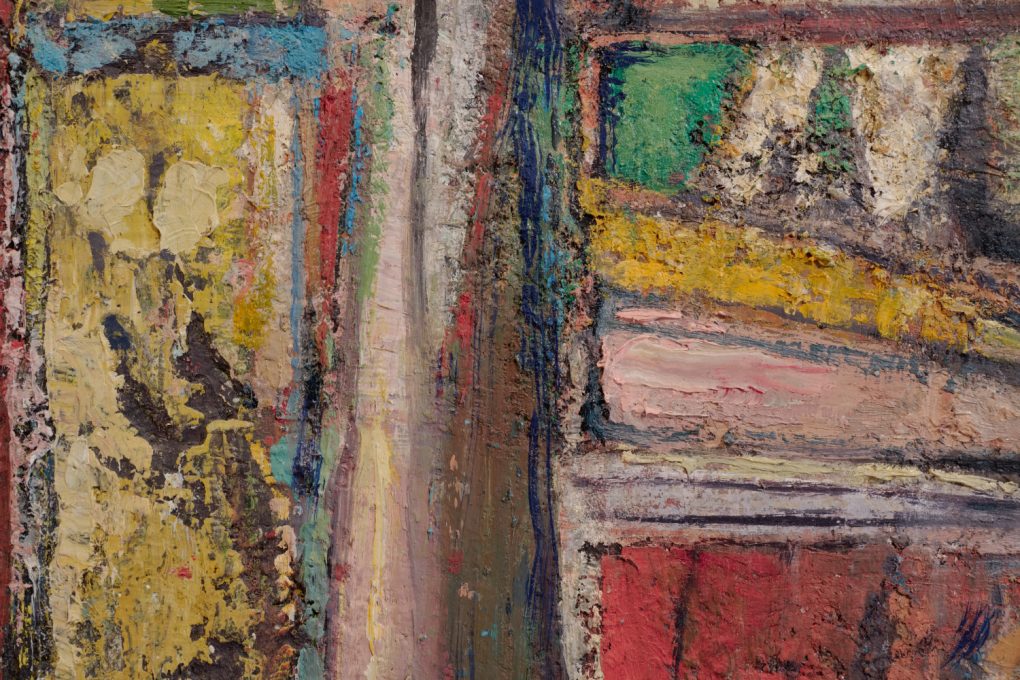

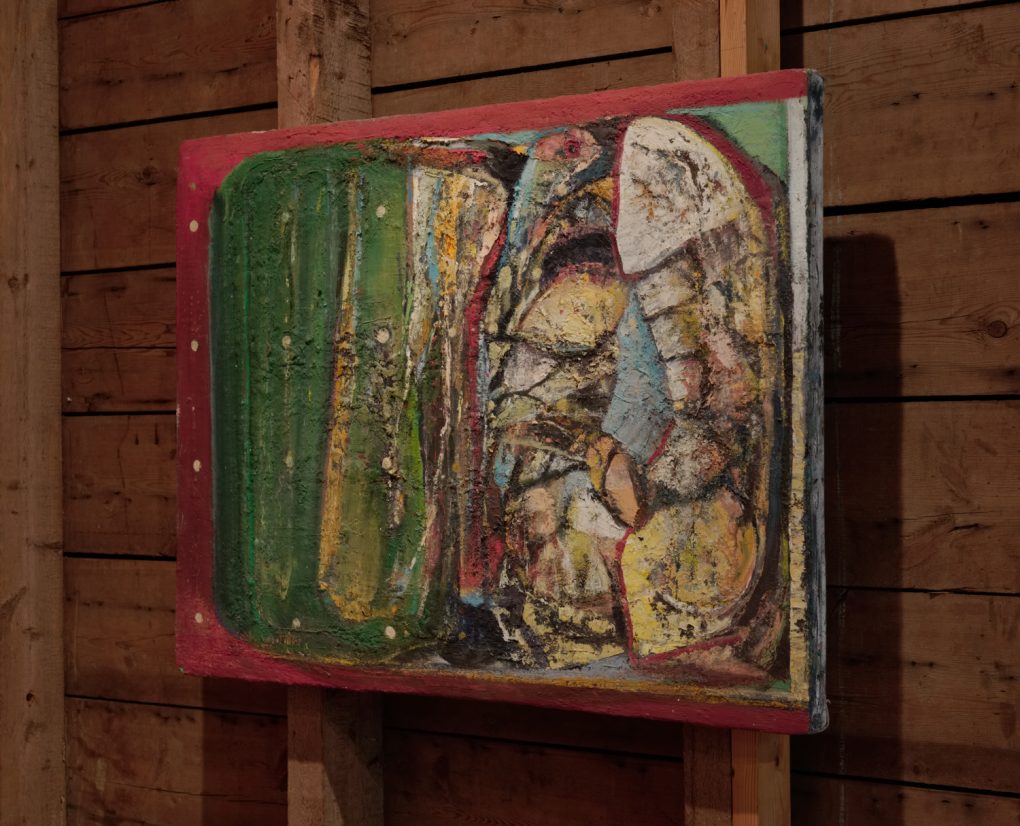

Red Sea, 2019, oil on canvas, 42×32″ and Alley, 2019, oil on canvas, 29×26″ from Three Painters at Duck Creek at the Arts Center at Duck Creek

Hiroyuki Hamada: What prompted you to pursue visual art? Was there any specific event that you can remember? Or was there a moment of realization that art is special to you?

Eric Banks: It’s hard to point to a particular event in my life that was the impetus for becoming an artist. I often think of Auden’s poem on the death of Yeats where he asserts “Mad Ireland hurt you into poetry” applying to myself in my own psychological need and the disillusionment I felt after going through a more political and activist period of idealism and action towards a hope for a better more equitable society, a parallel. (As in “Mad America or maybe more specifically “Mad Queens hurt me into poetry”)

As a child and teenager I always had a kind of peripheral interest in art but it always seemed to be something that wasn’t very primary in terms of the way I saw myself as a person going forward into the world. It was only later after a year or so in college when the structure of my family’s life came crashing down with the descent of my father into a protracted period of mental illness which ended in his early death at the age of 53 that I found in the pursuit of art a way to channel both my anger and pain and a growing interest in literature, psychology, and philosophy into a positive and meaningful direction.

I started reading literature and poetry most notably Albert Camus, T.S. Eliot, Wallace Stevens, and Allen Ginsberg among others, and I started initially to make sculpture under the tutelage of Tom Doyle, Jake Grossberg, and Larry Fane. I worked primarily in metal, clay, and wax, both figuratively and abstractly. I then gravitated towards drawing and painting and then went to graduate school in Baltimore studying with Grace Hartigan and Sal Scarpitta.

Red Sea, 2019, oil on canvas, 42×32″

Hiroyuki: I can certain relate to the path you’ve taken. I feel that there is a sense of liberation in pursuing art, as well as a sense of authenticity of working with real elements in real interactions. You really can’t deceive yourself about those dynamics if we are to reach a meaningful expression. Can you describe a bit more about how your pursuit developed? What prompted you to choose sculptures initially, and how did your interests shift to 2-dimensional work?

Eric: It’s hard to say that there was much intentionality to any of it. The events and course of my life were in such disarray and confusion at that time and certainly lacking in guidance either externally as in from parents or internally as in having had a sense of driven-ness. I sort of gravitated to taking a sculpture class with Tom Doyle and was immediately both attracted to the freedom and the depth of knowledge and history that was being presented. Tom was a guy from the Midwest, kind of a real country boy but with incredible sophistication as an artist. I didn’t know at the time that he had been married to Eva Hesse, didn’t even know at the time who she was. I actually didn’t know very much at all about contemporary art. I might’ve been impressed if I’d known that he had shared a studio with Roy Lichtenstein at Ohio State but probably not. Tom showed me a lot of images of sculpture and after having made a small piece in folded paper pronounced that I was a metal sculptor and proceeded to introduce me to a guy who was working in the shop(who was tripping on acid) asking him to show me how to weld and cut steel. As there was no specific class in metal sculpture at the time I pretty much had run of the place. For about a year, or year and a half I played around with steel and made sculpture. In that time I took some figurative sculpture with Jake Grossberg who was a brilliant and very tough teacher, and Larry Fane also brilliant but not as tough. They both looked at my metal work and gave me advice and encouragement.

But still at 21 I was still uncommitted and pursuing different avenues of expression. I began writing -sort of stream of consciousness stuff and attempts at poetry. I started to draw from the figure and became fascinated with the strange interrelationship between the mechanics and the poetry of space in a two-dimensional format. At the time the Queens College art department had a somewhat conservative focus but with a deep resonance of the New York School and in which most of its professors were educated and to some extent rebelled against. This was true mainly in the two-dimensional studies as the sculptors were more in step with contemporary developments. Though I struggled with my own rebellious nature I begin to learn something about drawing and perhaps more how one could channel one’s emotion and intellect through very simple means which were very accessible. As an indigent student I found this very attractive.

And as an organic flow from drawing I begin to try to paint. As I knew nothing and wasn’t an art major I just kind of floated around, took a couple of classes and sat in on many others including graduate seminars mostly with Rosemary Beck who was perceptive enough to see something in my awkwardness and lack of experience and was very encouraging. At this time I began a lifelong friendship with Glenn Goldberg with whom I shared a couple of apartments and a lot of art and life developing.

I began to look at a lot of painting in museums and in books and was most attracted to both the postimpressionists and the abstract expressionists and began to paint landscapes and still lives.

Alley, 2019, oil on canvas, 29×26″

Hiroyuki: You know, when I started to paint again a few years ago after working with sculptures for two decades, I felt the striking sense of freedom in spontaneously reacting in the making process, and seeing the process becoming the structure itself. I feel that it does allow me to express myself in a more intimate fashion. So I totally understand why your interests in existential matters could draw you to two-dimensional works.

I find your work very distinct in the way that the colors, textures, shapes and so on are very much tactile. And the cohesive structures seem to present solidness that allow viewers to grasp your work with an impact. Can you talk about some of the prominent features of your work? Can you describe what typical roles those elements play in your work? How do they relate to each other?

Eric: I’m very interested in materiality and the transcendent capacities of how paint functions both as color and form both illusionistically and physically. I suppose it’s an aspect of the fusion between one’s scientific nature or more physical interests and one’s poetic inclinations. I think we as humans are innately fascinated with the ability to make pictures that convey something, whether it’s an aspect of recognition, reminiscence or feeling, a hint at what is known in the subconscious or something more specific, but I think always when it’s really painting, at something subliminal even if it’s a painting of, you know, trees or a street, or a person, or apples and pears on the table. It’s probably a more complex dynamic when it comes to pure abstraction if there actually is such a thing. But I think it gets back to the same elemental aspect the same existential longing for a connection with some unknowable essence that is so paradoxically both familiar and universal.

And to your point on the structural cohesion in my work I think it relates to that dynamic of a comfort in a familiarity and recognition that I need to grasp onto when mining the depths of the unconscious.

Hiroyuki: The physicality of paint is certainly prominent in your work, but your equal interest in an illusionistic, or poetic, quality perhaps gives your work some sort of hyper presence that I recognize. As a sculptor who paints on the 3D surface, this is something I am very much aware of. And I like how you describe your basic momentum as an “existential longing for a connection with some unknowable essence that is so paradoxically both familiar and universal”. It really proves that there is something more to life than what we can perceive with our regular senses.

Factions, 2020, oil on canvas, 54×48″ and Point d’Arret, 2019, oil on canvas, 27×26″

Where do you think your work is going right now? What are you excited about?

Eric: As to direction? I don’t really think very often of where the work is going. I guess I’ve always relied on a more instinctual perhaps intuitive approach. It’s kind of like absorbing all of the stimuli, the physical, intellectual, spiritual and just allowing my processes to flow.

At times though and I think this is happening more frequently as I get older, a kind of intent is becoming more of a prominent aspect. I think I’ve always felt that for me art needs to serve some purpose beyond the decorative/illustrational, or the creation of objects of either commemoration or worship or meditation, though I do have some appreciation and interest in all of those functions.

For a time I thought that one could express all the aspects of human pathos and aspirations within the context of a shape or form in space, that with color and scale and touch and conception one could communicate just about anything without having to illustrate or deal in any way with recognizable imagery or metaphorical illusion. So now I think I go back and forth between anarchic flow that allows me to find forms to isolate in spaces to a more willful attempt towards a figuration that is more clearly symbolic or expressionistic and pointed.

The sculptural work when I resumed the activity kind of opened up a desire to be more direct in the formulation of my imagery, not that the forms are all that specifically anything depictive but more that the very physicality of 3 dimensionality lends a “presence” that is more immediately familiar. I’ve always thought my work to be about an attempt to achieve some sort of understanding of where the deeper aspects of human consciousness meet with the more prosaic. Also I think I have a growing desire to be less detached and more able to communicate what it is that I’m trying to say. Of course this isn’t all that easy as I’m not all that certain most of the time of what it is I’m really trying to say, which is why one of my favorite quotes is that of Samuel Beckett who said I think in “The Unnamable”-

“I no longer know who I am, or what I am doing.”

Perhaps it’s something of an attempt to reconcile the issues of being an artist for the reasons that I was originally drawn to Art and all of the subsequent issues of being an artist in the world, professionalism, the “Art world”, the commercialization – valuation, commodification. It’s like looking back in trying to recover that first blush of excitement all the time to somehow or other find that energy and courage that one had at the very beginning. Again one of my favorite quotes from a poem by Theodore Roethke – What Can I Tell My Bones?

“Beginner,

Perpetual beginner,

The soul knows not what to believe,”…

So I guess the best answer to that question would be just that to find a way back, back to a beginning back to a feeling, inspiration, and hope that that came out of perhaps a conflict between ones idealism – pain, cynicism, hope, faith?

Factions, 2020, oil on canvas, 54 x 48″

Hiroyuki: That’s a really fascinating observation. We could perhaps theorize that a duality in a given dynamic is always a part of something that can be identifiable. When something is going to take a shape at all, it needs a background. And depending on your view, it is debatable what is foreground or background. And indeed, there might be a curious attraction in having a recognizable expression as a part of the dynamics, sort of bridging the unknown and what we can recognize.

But getting back to the dynamic, perhaps, as we shift our perspective continuously, in order to figure out the totality of the wholeness, ultimately, we become one with the phenomenon, resulting in a disappearance of self as we recognize the essence.

I wonder if this sort of intimate engagement with elements around us might be harder, if possible at all, as we must operate within our social framework which is artificial with its imperatives serving the rich and powerful.

This provokes many existential questions particularly for artists who wish to be a part of a constructive force of our time. I very much appreciate you sharing your insights and perspectives for this conversation. Do you have anything to add?

Eric: I suppose it’s always in vacillation, with the world and the attempt to access something more of a pure mind. And of course the current distractions of technology and the bombardment of media makes it that much harder to find the silence of a wished for ideal state. Perhaps I’m not even sure of the relevance in that pursuit or sublimation. At a certain level I’ve always felt that my work might almost serve as a kind of seismograph of being measuring anxiety against a sense of freedom, sadness, joy, pain, pleasure. And all of these things serve both as to the functions and processes of the world outside of both one’s immediate life experience and even those outside of one’s historical or social context. Or if one looks at things from the standpoint of seeking truth there’s still the need for reconciliation with perception and how prepared one is to understand what that even means. Wallace Stevens ends his famous poem “The Man in the Dump” with the line “Where was it one first heard the truth, the, the.” In essence we’re all kind of picking through the trash bins of history seeking treasures of sorts seeking wisdom and enlightenment at the same time as being immersed in our actual experience with its beauties and its terrors, it’s emotions and it’s thoughts, observations, memories and dreams.

So I’m not really after any kind of purity anymore, maybe I never really was, perhaps more a kind of distillation to something that seems essential in something that is evocative maybe something even that disturbs, provokes, and maybe instills some connection that might initiate a human response.

Point d’Arret, 2019, oil on wood, 27 x 26″

Eric Banks(b. 1954 Brooklyn, NY) is a Brooklyn-native and lives and works in Rhinebeck, NY. In 1977, he obtained his B.A. from Queens College of the City University of New York, NY. In 1981 he received his M.F.A. from Maryland Institute College of Art, Hoffberger School of Painting. Banks has been awarded the Pollock-Krasner Foundation Grant, Edward Albee Foundation Grant, and Walters Fellowship. He has exhibited nationally; most-recently, his work has been on view at NYC galleries, such as Amos Eno Gallery and Sideshow Gallery.