-

Conversation with Sean Sullivan

Here is an interview I have done with artist Sean Sullivan. Sean is one of the artists in the show Three Painters at Duck Creek, which I curated for the Arts Center at Duck Creek. I enjoyed our conversation tremendously and I thank Sean for being a part of the fantastic show.

Sean Sullivan’s paintings from Three Painters at Duck Creek. Here is a list of works at the Arts Center at Duck Creek site.Hiroyuki: How did you come to pursue visual art? Do you remember a special moment or a series of events that convinced you that this is something you want to do with your life?

Sean: I really came to art – drawing, writing poetry as a teenager right around the time I discovered music. Music opened my world up – gave me an awareness beyond my own experience. It’s always been and still is a very important part of the process for me.

As a teenager I was too shy to get up and sing songs so I channeled my energy into drawing and writing poetry. It felt like I was sending signals to unseen allies from behind enemy lines (still does). Drawing and writing poetry in a notebook felt possible to me somehow – both so close to the ‘self’ – idiosyncratic like handwriting. In other words, no one could tell me I was doing it wrong. Intelligence didn’t matter, training didn’t matter. I could pursue these ‘secret’ activities in earnest, at all times – even while in the classroom listening to the teacher or later on the job or traveling on a train, etc.

Coincidentally as I write this on Father’s Day – it was my father who really pushed me to pursue art and the creative life. He really believed in me and told me every chance he got.Hiroyuki: I like how you as a child recognized the essential quality of art to be an expression of who you are for those who can accept you as who you are. Ultimately, I think this is one of the fundamental aspects of art that validates its meaning in our society today. In fact, your work does resonate in me at some deeper levels.

I’ve learned that you have a special process that’s in between painting and print making. Could you describe how it works and what it does? And how you came across it and why?

Sean: I began using the oil transfer process about ten years ago. I came to it by accident – out of frustration really. Basically I apply oil stick to a sheet of newsprint and thin it out with a silkscreen squeegee until it resembles something like carbon paper. I then place the found paper face down on top of the oil transfer paper and make a drawing on the reverse of the found paper with a Bic ballpoint pen. Each color in a finished piece is represented by a different sheet of oil transfer paper – a hybrid sort of drawing/printmaking process.

Over the years the process has refined some and evolved conceptually as I began to think of this process akin to plate photography and musical recordings.

I use ‘found paper’ not out of some nostalgic yearning but because I find new paper to be kind of cold and homogenized. The history embedded (the marks and color) in found paper give me a head start somehow – something to react to. I source the found paper mostly from books (used bookstores and antique stores) that I either buy or many times friends pass along.

Sean Sullivan’s paintings from Three Painters at Duck Creek. Here is a list of works at the Arts Center at Duck Creek site. Carnival, 2020, Oil on found paper, Unframed: 7.75 x 10.5” / Framed: 10 x 14”

Carnival, 2020, Oil on found paper, Unframed: 7.75 x 10.5” / Framed: 10 x 14”Hiroyuki: So you have a real setting with its history and characters somehow when you start. And your action is an interaction with it as much as your own narrative coming out of your psyche. And perhaps the print aspect allows your process to manifest in unexpected, yet organic ways? And what about the imageries?

Sean: Yes exactly. The history embedded in the paper offers a starting point and the process allows for both predictability as well as improvisation. The imagery is improvisational – instinctual even if I try and start with a plan it always goes off track and I just go with it. A piece usually falls flat if I’m trying too hard to ‘do’ something – to control the outcome. Hope that makes sense.

Hiroyuki: It certainly does. How do you describe your improvisational process? Could you describe your work environment for the readers?

Sean: I think improvisation begins before you even sit down to work. It’s an exercise in faith or the practice of faith maybe? I don’t mean that in a religious sense per se, but faith in ability, in intention and in good outcomes. A trust that you can make something from nothing and even if there are ‘mistakes’ or setbacks, by adjusting expectations you can land in a more unexpected, inspired place. There is no right, there is no perfect and starting from that point – everything, every mark makes sense and has a place.

My studio is full of natural light and close to the family – a small sun porch attached to our living room. Marie and the kids are in and out all the time. It’s a perfect situation for me – I need them close by. The paint I use, R&F Pigment Sticks, I make for a living (for the past 13 years). It’s all close by I guess.

Sean Sullivan’s paintings from Three Painters at Duck Creek. Here is a list of works at the Arts Center at Duck Creek site.

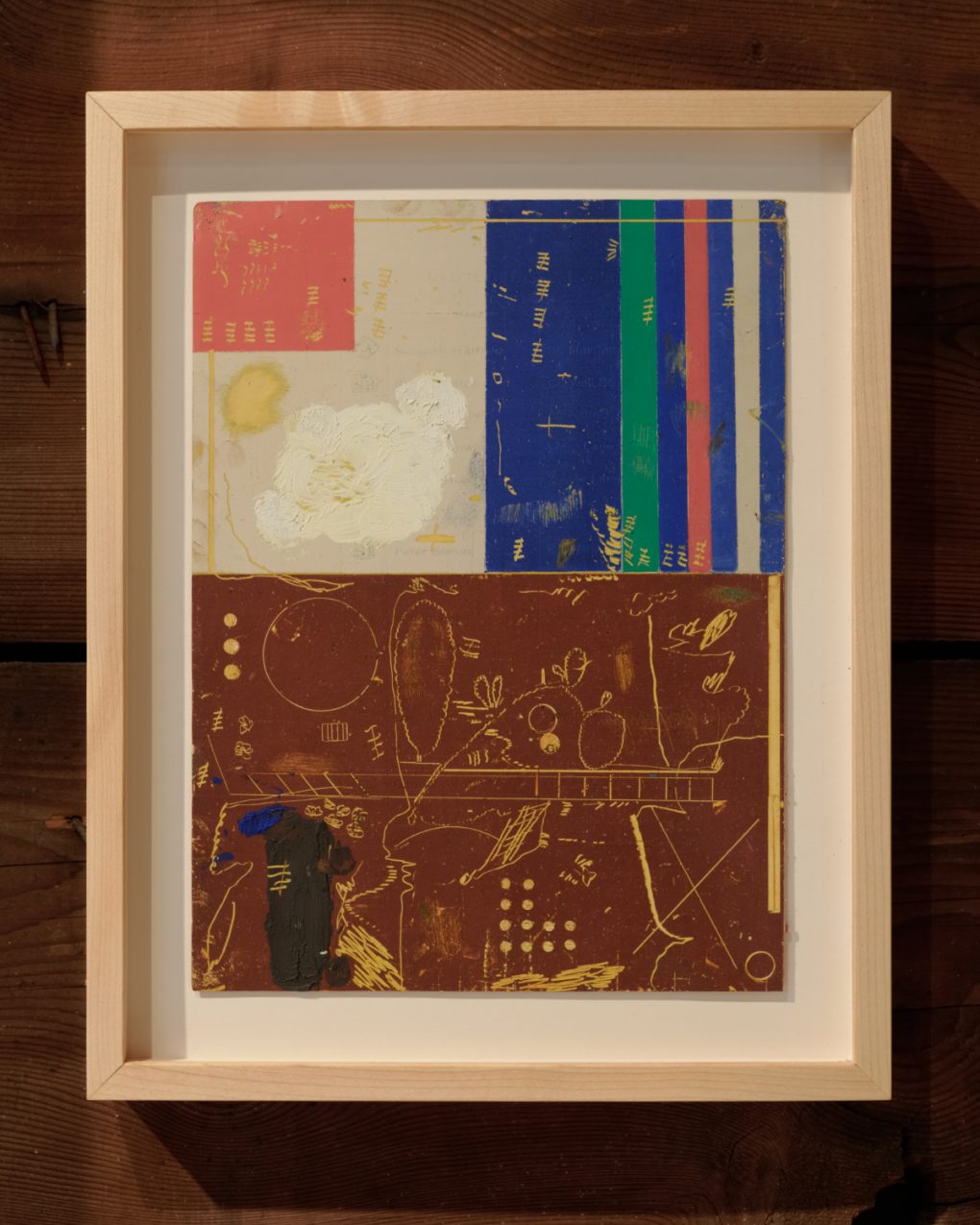

Sean Sullivan’s paintings from Three Painters at Duck Creek. Here is a list of works at the Arts Center at Duck Creek site. Rodriguez Solitaire, 2019, Oil on found paper, Unframed: 8.5 x 12” / Framed: 11.5 x 14.5”

Rodriguez Solitaire, 2019, Oil on found paper, Unframed: 8.5 x 12” / Framed: 11.5 x 14.5”Hiroyuki: I like that. There is an element of faith in facing the unknown as we make. When I visited you last time, it was eye-opening to see your work being so much a part of your family. This also extends to your position at R&F Pigment Sticks. Instead of seeing the creative process as an opposing element against your circumstance, you have put good efforts in creating an environment that enhances your work as much as your life and people you love. I think this is very significant in terms of making your “faith” grounded to your reality.

In your booklet “This Means I Always Have Something to Do. A Conversation Between Sean Sullivan & John Yau” you talked about differences between working within set conditions as opposed to being more flexible and organic. To me it seemed that you are good at putting your life in a cohesive framework so that you can be free within it.

Now, I assume that you must have challenges on your path. Could you describe some of the biggest obstacles and how you deal with them?

Sean: My apologies for taking so long to respond to this question – time is elusive! which brings me to a challenge I’ve always faced (I think many of us face) which is time – finding the time to make work. At this point I’ve come to terms with the limitations and to be honest if I had ‘all the time in the world’ I’m not so sure I’d be making better work or more work. Having said that I would like more time in the studio – even just for looking, moving things around – thinking. Another challenge I’d have to say is doubt – at times, extreme doubt – I think in some ways the other side of the coin so to speak. Normally I make work and don’t look back but every now and again I do turn and take stock and that can be sobering. I do have to say through all of these challenges I feel very, very lucky to make work and to share work and for all the talented, devoted individuals that I’ve had the opportunity to work with – galleries, artists, etc. and that I get to continue to make work and maintain balance in our family life is so important. I’m grateful.

Fairgrounds, 2018, Oil on found paper, Unframed: 6 x 8” / Framed: 8.5 x 10.5”

Fairgrounds, 2018, Oil on found paper, Unframed: 6 x 8” / Framed: 8.5 x 10.5” Things huddled together surrounded by uncertainty, 2019, Oil on found paper, Unframed: 7.5 x 11” / Framed: 10.5” x 13.75”

Things huddled together surrounded by uncertainty, 2019, Oil on found paper, Unframed: 7.5 x 11” / Framed: 10.5” x 13.75”

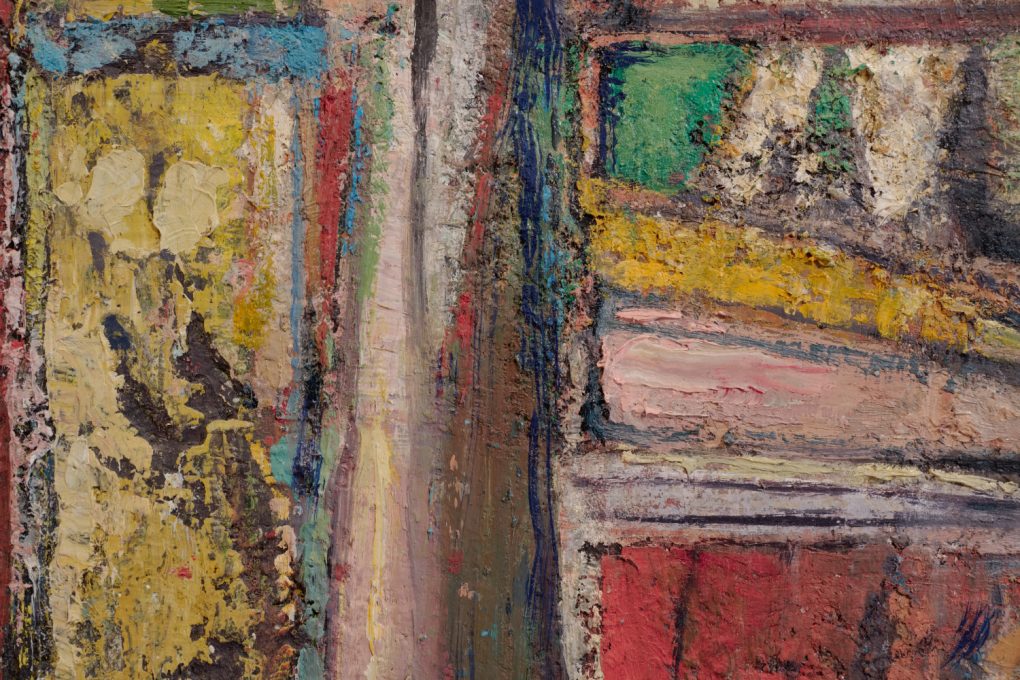

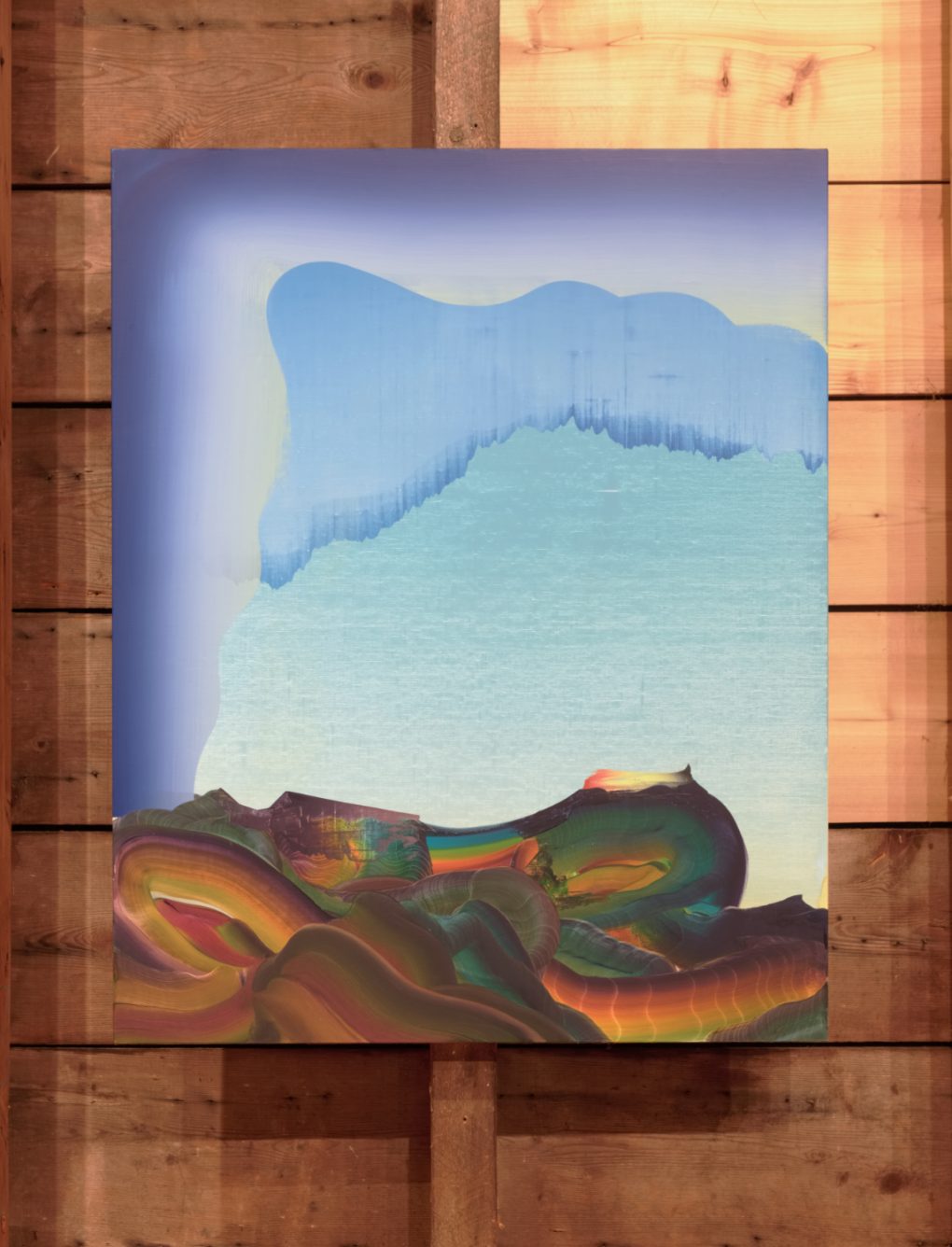

Sean Sullivan’s paintings from Three Painters at Duck Creek. Here is a list of works at the Arts Center at Duck Creek site. Futures, 2018, Oil on panel Unframed: 36 x 48″

Futures, 2018, Oil on panel Unframed: 36 x 48″Hiroyuki: You said “doubt–at times, extreme doubt”. Could you elaborate?

Sean: I think doubt in the studio, in life, extreme or otherwise, goes hand in hand with those moments of clarity and inspiration – grace. Time is really the salve. I think you just have to get through it, work through it, until there’s a ‘break in the clouds’. Maybe just the natural order of things – balance. Sometimes I think my doubt stems from not understanding where the work comes from so the ownership of it – the ego is thwarted a bit. If you didn’t ‘think of it’ then maybe you can’t entirely claim credit for it. Where does that leave you as an artist? An ‘originator’. But that is also what I love most about the process. The unknown – the mystery of it. This also works in reverse for me. What I mean by that is if I do have an idea, a ‘concept’ meaning the ego wants to direct the inspiration – it almost always (in my experience) leads to frustration and disappointment. I will say those excursions into frustration and disappointment are not fruitless and often lead to things unexpected – breakthroughs even.

Hiroyuki: Yes indeed, I feel what you are saying. Our perceptions seem to struggle at times, clouded by our immediate interests or lack of understanding, or often both. But, paradoxically, those obstacles also prompt us to explore and seek cohesive expressions that somehow resonate with us. In doing so we struggle to see and we face the unknown in an honest manner. This I regard as one of the most crucial aspects of the making process, which I believe resonates with our struggle in how to be.

Thank you so much for the fascinating conversation and I look forward to seeing more of your fantastic work.

Sean Sullivan’s paintings from Three Painters at Duck Creek. Here is a list of works at the Arts Center at Duck Creek site.Sean Sullivan (b. 1975 Bronx, NY) lives and works in the Hudson Valley, NY. He received the NYSCA/NYFA Artist Fellow in Printmaking/Drawing/Book Arts Grant in 2017. Sullivan has participated in group exhibitions at the Samuel Dorsky Museum of Art at SUNY New Paltz, NY; the Markus Luttgen Gallery, Cologne, Germany; and the Museum for Drawing, Huningen, Belgium.

-

Conversation with Elliott Green

Here is an interview I have done with artist Elliott Green. Elliott is one of the artists in the show Three Painters at Duck Creek, which I curated for the Arts Center at Duck Creek. I enjoyed our conversation tremendously and I thank Elliott for being a part of the fantastic show.

Paintings by Elliott Green from Three Painters at Duck CreekHiroyuki: What prompted you to pursue visual expression?

Elliott: In college I was majoring in literature, but a girlfriend of mine ran the slide projector for art history lectures, so I sat in on those classes, and in the dark lecture halls I was gratefully transfixed and transported through time and all over the world. It was a beautiful escape, and I started to draw in my notebooks, and finally dropped out of the University of Michigan in my third year to move to New York City to learn how to paint. When I landed there in the summer of 1981, I took a couple of month-long courses at the Art Students League, then painted on my own ever after.

Hiroyuki: So, you felt it was a “beautiful escape” when you saw the images in the art history classes. Were you conscious about what you were escaping from? Did the momentum to quit school and move to NYC have anything to do with it, or were you simply under the spell of what art could do for you?

Elliott: That’s a very good question! I was bored and frustrated: mostly with myself, the Midwest where I grew up, and my waning interest in writing fiction. I felt I was in a holding pen — and I had ambitions to do something good and tangible — to test and prove my Self in the larger world; but I didn’t know how that was going to take shape. I was inexperienced. I was immature and impatient. But it turns out that I did find my life’s work after all — in making paintings.

Dressmaker, 2011, Oil on linen, 43 x 40″Hiroyuki: It sounds like you had something in you that needed to come out. Naturally, I think of the explosive energy, poised serenity, and exquisite dynamism of your current work. The colors, movements and rhythms are just bursting out of the canvases. I’ve read that the current direction emerged after your trip to Rome as well as your move to Athens, New York. What do you think has allowed you to be expressive in this way? It seems that your interests in visual elements themselves has been liberated, as opposed to your former expression through recognizable figures, the narratives and more limited usage of visual elements.

Elliott: Actually, catharsis has been a leitmotif in my work, and that was probably something I gleaned from studying literature and film. Often in my paintings — from out of some placid zone of quiet painting–a loud gestural eruption occurs. It’s dramatic, and it’s something I can do by heightening or lowering my physical — my muscular and emotional energy, like a musician or an actor. Another narrative that occurs a lot is to have a constricted space that blasts open into a vaster one. A remarkable thing happened in Rome: the density and compression of the two-dimensional abstract paintings I had been making for several years expanded outward when that information was transposed into the landscape format, into perspective: that was like an explosion. The additional space gave the previously contained subject matter freedom to move from the distance to the forefront, and it was like an infusion of fresh air. It was liberating. And the shapes, like the round or sharp ones of the mountains, took on characteristics–recognizable personalities–like the figures I had painted years before.

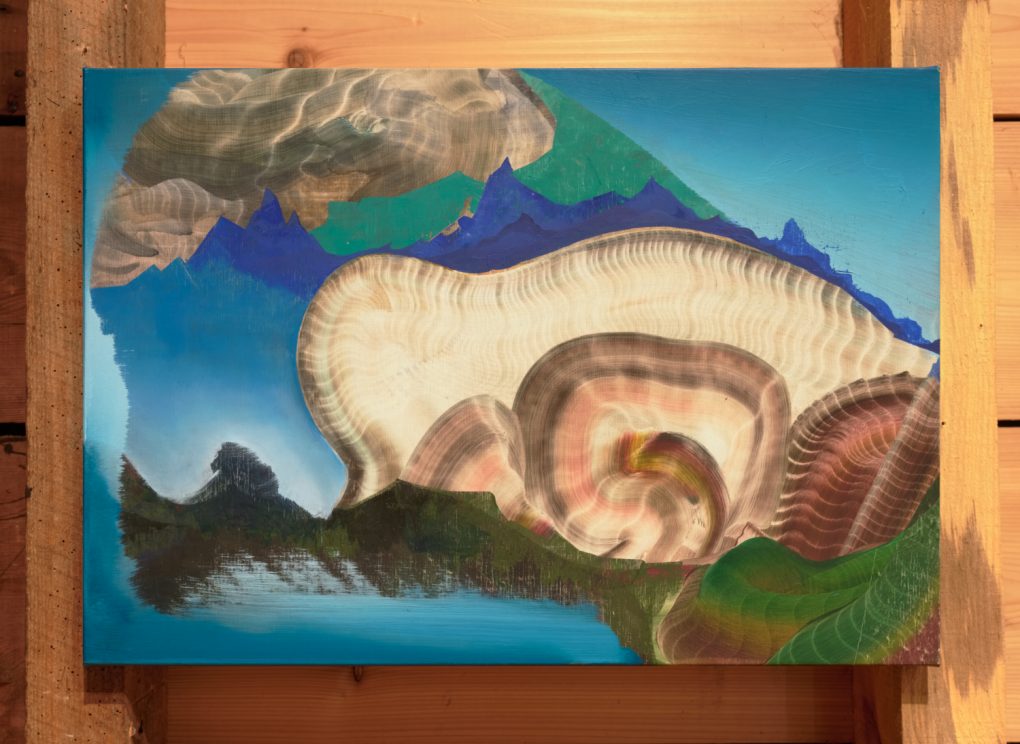

Beach Mountain 2015, Oil on linen, 76 x 54″Hiroyuki: The reference to landscape does work wonderfully to express the vast scale while also putting the element of time in a geological time frame. Combined with rich visual characters weaving narratives, the dramatic expression certainly brings out a strong emotional quality. But then, all that merely presents a challenge of actually constructing a functional whole which you manage very well. How does your painting start? Can you describe your making process? Also, were you always interested in colors? The striking use of colors can be seen as playful and absurd. In a way, it echoes your use of figures in your previous work.

Elliott: I start by brush-sketching on the canvas with a mixture of oil paint and graphite, and sometimes added colors, and I move without conscious intention for meaning, seemingly randomly, wiping away a lot. There is no pressure, because it is impossible to make a mistake at this stage. On one level, it is warming up my muscles, relaxing, emotionally diffusing, and at very least, spreading the tone on the canvas. If I make sweeping gestures that transverse the entire space, that will precede the final composition somehow, and foreshadow a theme. Motifs of shapes occur and through addition and subtraction some sensibility, personality and perspective arrive, and then I do more conscious analysis – editing, adding and tweaking to focus on the most interesting aspects and activities. For the benefit of the whole painting, some beautiful passages have to be sacrificed and painted over. Somehow, given enough time, a coherent vision arrives. I’ve made stop-action films of me making my paintings – and those let a viewer see how many decisions, reversals and revisions are involved, all of them impossible to predict.

I think I always had a sense of which colors got along beautifully with each other. I remember staring at children’s books as a toddler, immersed in them, like I was fascinated by their tonal harmonies. But not long after I began painting as an adult, I was looking for more excitement, and one way is to use colors that are unappealing on their own and to put them in with the naturally beautiful ones: the result is often very interesting. For example, the pink and green used to seem like a viscerally offensive combination to me, maybe because it reminded me of insects or rancid meat. But that is exactly where the meaning resides in color, in its good or bad associations with aspects of the world. A rainbow means connection and vomit means rejection — that’s good content even by itself, and then more dramatic when they conflict, or even better, if they somehow become unlikely friends.

Fungus, 2018, Oil on linen, 16×24″ and Interesting Dirt, 2019, Oil on linen, 40×30″Hiroyuki: I just saw the videos that show the progress at your site. I can relate to the dialogue you create with the dynamics. I know that there are moments of excitement, disappointment, frustration, a sense of achievement and so on. And there is nothing like feeling that everything merges as the process culminates in presenting a cohesive wholeness. I don’t always feel it but sometimes the moment is indeed a catharsis. And it is also fascinating that the complex dynamics often reveal “unlikely friends”, as you say, it strikes us with unknown chemistry in viscerally concrete ways. It allows us to explore and makes us see unknown potentials explode before us. Strange thing isn’t it? Are there any activities that go with your studio practice? I mean, everything ultimately does, but things you are conscious about to keep you going.

Elliott: I realized in Rome, where my eyeballs were literally aching from looking so hard, that new environments absolutely stimulate what I will paint. I think it’s because when shapes and tones fill my short-term memory to capacity, it speeds up my decision-making, and the improvisations flow faster. So, my method is to just look around me with an innocent curiosity. I never deliberately seek out material for painting, nor do I sketch with the intention of inserting some phenomena directly into a painting. I have to be honestly, genuinely compelled by something to study it and enjoy it for itself, and then maybe, sooner or later, some essence of that thing I was paying attention to will emerge effortlessly at just the right time and place in a painting.

Interesting Dirt, 2019, Oil on linen, 40 x 30″Hiroyuki: I’ve heard artists talking about appreciating things around us visually. I always thought it was more about our attitude toward life in a general sense. But that makes sense. We learn and we are conditioned by our environment. Our actions and thoughts are affected by those. I was just talking to Eric Banks and he was also saying that he paints landscape paintings to inform himself about visual structures. And by choosing what to look at and how you look at it, you make a conscious decision (to a certain extent) as to where you sharpen your craft of expressing visually. That’s very interesting. It makes me think that artists should talk to each other more. Do you feel that you belong to an art community?

Elliott: Before a gallery represented my work in New York, I had no artist friends. But after 1989, when I was 29, I met many artists, mostly at first through another painter and sculptor named David Humphrey, who is very popular and active in the art community. He’s what the sociologists call a Super Connector.

Pierogi, the gallery where I show in NYC, is run and owned by a couple, an artist and a poet, so there is a lot of mutual respect, and also camaraderie among the artists who show there. The openings at Pierogi have always been packed with many artists. Joe Amrhein, the co-director, had a show at Postmasters Gallery in Tribeca last year. His paintings are great, but he also thinks of the gallery as a long running conceptual artwork about the moving messages of contemporary artists. There have been many historical shows there — it was the most active gallery in Williamsburg for decades, before they moved to the Lower East Side a few years ago. Its existence has documented the emergence of that neighborhood as a cultural community. Many of the artists that show there are my friends. And then I have made new friends, like you, on Instagram, which has really widened my horizons by introducing me to the work of friends of friends and talented people outside my generation, younger and older.

Hiroyuki: Elliott, thank you for sharing your insights and angles on many topics on art and art communities. Do you have anything to add to our conversation?

Elliott: Not really. Just thank you for this chance to think about my work from a fresh perspective, and for your interest. I think your work is great, and it has been enjoyable to compare notes on the shape of our different quests, and to see how our work has arrived at its present place.

Fungus, 2018, Oil on linen, 16 x 24″Elliott Green (b. 1960 Detroit, Michigan) attended the University of Michigan, where he studied World Literature and Art History. He moved to New York City in 1981 and has been awarded a John Simon Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship, the Jules Guerin Rome Prize at the American Academy in Rome, a Pollock-Krasner Foundation Grant, a Marie Walsh Sharpe Foundation Residency, The Peter S. Reed Foundation Grant, a residency at the BAU Institute, Cassis, France, a MacDowell Colony Residency, and three residencies at Yaddo.

-

Conversation with Eric Banks

Here is an interview I have done with artist Eric Banks. Eric is one of the artists in the show Three Painters at Duck Creek, which I curated for the Arts Center at Duck Creek. I enjoyed our conversation tremendously and I thank Eric for being a part of the fantastic show.

Red Sea, 2019, oil on canvas, 42×32″ and Alley, 2019, oil on canvas, 29×26″ from Three Painters at Duck Creek at the Arts Center at Duck CreekHiroyuki Hamada: What prompted you to pursue visual art? Was there any specific event that you can remember? Or was there a moment of realization that art is special to you?

Eric Banks: It’s hard to point to a particular event in my life that was the impetus for becoming an artist. I often think of Auden’s poem on the death of Yeats where he asserts “Mad Ireland hurt you into poetry” applying to myself in my own psychological need and the disillusionment I felt after going through a more political and activist period of idealism and action towards a hope for a better more equitable society, a parallel. (As in “Mad America or maybe more specifically “Mad Queens hurt me into poetry”)

As a child and teenager I always had a kind of peripheral interest in art but it always seemed to be something that wasn’t very primary in terms of the way I saw myself as a person going forward into the world. It was only later after a year or so in college when the structure of my family’s life came crashing down with the descent of my father into a protracted period of mental illness which ended in his early death at the age of 53 that I found in the pursuit of art a way to channel both my anger and pain and a growing interest in literature, psychology, and philosophy into a positive and meaningful direction.

I started reading literature and poetry most notably Albert Camus, T.S. Eliot, Wallace Stevens, and Allen Ginsberg among others, and I started initially to make sculpture under the tutelage of Tom Doyle, Jake Grossberg, and Larry Fane. I worked primarily in metal, clay, and wax, both figuratively and abstractly. I then gravitated towards drawing and painting and then went to graduate school in Baltimore studying with Grace Hartigan and Sal Scarpitta.

Red Sea, 2019, oil on canvas, 42×32″Hiroyuki: I can certain relate to the path you’ve taken. I feel that there is a sense of liberation in pursuing art, as well as a sense of authenticity of working with real elements in real interactions. You really can’t deceive yourself about those dynamics if we are to reach a meaningful expression. Can you describe a bit more about how your pursuit developed? What prompted you to choose sculptures initially, and how did your interests shift to 2-dimensional work?

Eric: It’s hard to say that there was much intentionality to any of it. The events and course of my life were in such disarray and confusion at that time and certainly lacking in guidance either externally as in from parents or internally as in having had a sense of driven-ness. I sort of gravitated to taking a sculpture class with Tom Doyle and was immediately both attracted to the freedom and the depth of knowledge and history that was being presented. Tom was a guy from the Midwest, kind of a real country boy but with incredible sophistication as an artist. I didn’t know at the time that he had been married to Eva Hesse, didn’t even know at the time who she was. I actually didn’t know very much at all about contemporary art. I might’ve been impressed if I’d known that he had shared a studio with Roy Lichtenstein at Ohio State but probably not. Tom showed me a lot of images of sculpture and after having made a small piece in folded paper pronounced that I was a metal sculptor and proceeded to introduce me to a guy who was working in the shop(who was tripping on acid) asking him to show me how to weld and cut steel. As there was no specific class in metal sculpture at the time I pretty much had run of the place. For about a year, or year and a half I played around with steel and made sculpture. In that time I took some figurative sculpture with Jake Grossberg who was a brilliant and very tough teacher, and Larry Fane also brilliant but not as tough. They both looked at my metal work and gave me advice and encouragement.

But still at 21 I was still uncommitted and pursuing different avenues of expression. I began writing -sort of stream of consciousness stuff and attempts at poetry. I started to draw from the figure and became fascinated with the strange interrelationship between the mechanics and the poetry of space in a two-dimensional format. At the time the Queens College art department had a somewhat conservative focus but with a deep resonance of the New York School and in which most of its professors were educated and to some extent rebelled against. This was true mainly in the two-dimensional studies as the sculptors were more in step with contemporary developments. Though I struggled with my own rebellious nature I begin to learn something about drawing and perhaps more how one could channel one’s emotion and intellect through very simple means which were very accessible. As an indigent student I found this very attractive.

And as an organic flow from drawing I begin to try to paint. As I knew nothing and wasn’t an art major I just kind of floated around, took a couple of classes and sat in on many others including graduate seminars mostly with Rosemary Beck who was perceptive enough to see something in my awkwardness and lack of experience and was very encouraging. At this time I began a lifelong friendship with Glenn Goldberg with whom I shared a couple of apartments and a lot of art and life developing.

I began to look at a lot of painting in museums and in books and was most attracted to both the postimpressionists and the abstract expressionists and began to paint landscapes and still lives.

Alley, 2019, oil on canvas, 29×26″

Hiroyuki: You know, when I started to paint again a few years ago after working with sculptures for two decades, I felt the striking sense of freedom in spontaneously reacting in the making process, and seeing the process becoming the structure itself. I feel that it does allow me to express myself in a more intimate fashion. So I totally understand why your interests in existential matters could draw you to two-dimensional works.I find your work very distinct in the way that the colors, textures, shapes and so on are very much tactile. And the cohesive structures seem to present solidness that allow viewers to grasp your work with an impact. Can you talk about some of the prominent features of your work? Can you describe what typical roles those elements play in your work? How do they relate to each other?

Eric: I’m very interested in materiality and the transcendent capacities of how paint functions both as color and form both illusionistically and physically. I suppose it’s an aspect of the fusion between one’s scientific nature or more physical interests and one’s poetic inclinations. I think we as humans are innately fascinated with the ability to make pictures that convey something, whether it’s an aspect of recognition, reminiscence or feeling, a hint at what is known in the subconscious or something more specific, but I think always when it’s really painting, at something subliminal even if it’s a painting of, you know, trees or a street, or a person, or apples and pears on the table. It’s probably a more complex dynamic when it comes to pure abstraction if there actually is such a thing. But I think it gets back to the same elemental aspect the same existential longing for a connection with some unknowable essence that is so paradoxically both familiar and universal.

And to your point on the structural cohesion in my work I think it relates to that dynamic of a comfort in a familiarity and recognition that I need to grasp onto when mining the depths of the unconscious.

Hiroyuki: The physicality of paint is certainly prominent in your work, but your equal interest in an illusionistic, or poetic, quality perhaps gives your work some sort of hyper presence that I recognize. As a sculptor who paints on the 3D surface, this is something I am very much aware of. And I like how you describe your basic momentum as an “existential longing for a connection with some unknowable essence that is so paradoxically both familiar and universal”. It really proves that there is something more to life than what we can perceive with our regular senses.

Factions, 2020, oil on canvas, 54×48″ and Point d’Arret, 2019, oil on canvas, 27×26″

Where do you think your work is going right now? What are you excited about?Eric: As to direction? I don’t really think very often of where the work is going. I guess I’ve always relied on a more instinctual perhaps intuitive approach. It’s kind of like absorbing all of the stimuli, the physical, intellectual, spiritual and just allowing my processes to flow.

At times though and I think this is happening more frequently as I get older, a kind of intent is becoming more of a prominent aspect. I think I’ve always felt that for me art needs to serve some purpose beyond the decorative/illustrational, or the creation of objects of either commemoration or worship or meditation, though I do have some appreciation and interest in all of those functions.

For a time I thought that one could express all the aspects of human pathos and aspirations within the context of a shape or form in space, that with color and scale and touch and conception one could communicate just about anything without having to illustrate or deal in any way with recognizable imagery or metaphorical illusion. So now I think I go back and forth between anarchic flow that allows me to find forms to isolate in spaces to a more willful attempt towards a figuration that is more clearly symbolic or expressionistic and pointed.

The sculptural work when I resumed the activity kind of opened up a desire to be more direct in the formulation of my imagery, not that the forms are all that specifically anything depictive but more that the very physicality of 3 dimensionality lends a “presence” that is more immediately familiar. I’ve always thought my work to be about an attempt to achieve some sort of understanding of where the deeper aspects of human consciousness meet with the more prosaic. Also I think I have a growing desire to be less detached and more able to communicate what it is that I’m trying to say. Of course this isn’t all that easy as I’m not all that certain most of the time of what it is I’m really trying to say, which is why one of my favorite quotes is that of Samuel Beckett who said I think in “The Unnamable”-

“I no longer know who I am, or what I am doing.”

Perhaps it’s something of an attempt to reconcile the issues of being an artist for the reasons that I was originally drawn to Art and all of the subsequent issues of being an artist in the world, professionalism, the “Art world”, the commercialization – valuation, commodification. It’s like looking back in trying to recover that first blush of excitement all the time to somehow or other find that energy and courage that one had at the very beginning. Again one of my favorite quotes from a poem by Theodore Roethke – What Can I Tell My Bones?“Beginner,

Perpetual beginner,

The soul knows not what to believe,”…So I guess the best answer to that question would be just that to find a way back, back to a beginning back to a feeling, inspiration, and hope that that came out of perhaps a conflict between ones idealism – pain, cynicism, hope, faith?

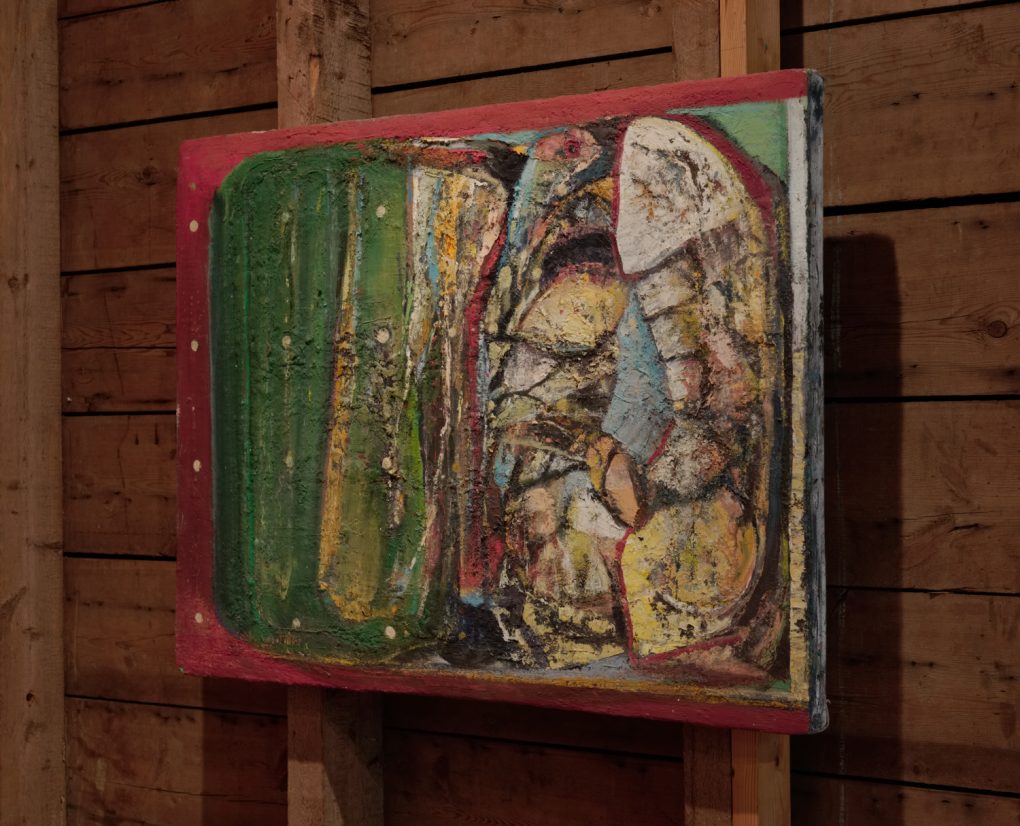

Factions, 2020, oil on canvas, 54 x 48″Hiroyuki: That’s a really fascinating observation. We could perhaps theorize that a duality in a given dynamic is always a part of something that can be identifiable. When something is going to take a shape at all, it needs a background. And depending on your view, it is debatable what is foreground or background. And indeed, there might be a curious attraction in having a recognizable expression as a part of the dynamics, sort of bridging the unknown and what we can recognize.

But getting back to the dynamic, perhaps, as we shift our perspective continuously, in order to figure out the totality of the wholeness, ultimately, we become one with the phenomenon, resulting in a disappearance of self as we recognize the essence.

I wonder if this sort of intimate engagement with elements around us might be harder, if possible at all, as we must operate within our social framework which is artificial with its imperatives serving the rich and powerful.

This provokes many existential questions particularly for artists who wish to be a part of a constructive force of our time. I very much appreciate you sharing your insights and perspectives for this conversation. Do you have anything to add?

Eric: I suppose it’s always in vacillation, with the world and the attempt to access something more of a pure mind. And of course the current distractions of technology and the bombardment of media makes it that much harder to find the silence of a wished for ideal state. Perhaps I’m not even sure of the relevance in that pursuit or sublimation. At a certain level I’ve always felt that my work might almost serve as a kind of seismograph of being measuring anxiety against a sense of freedom, sadness, joy, pain, pleasure. And all of these things serve both as to the functions and processes of the world outside of both one’s immediate life experience and even those outside of one’s historical or social context. Or if one looks at things from the standpoint of seeking truth there’s still the need for reconciliation with perception and how prepared one is to understand what that even means. Wallace Stevens ends his famous poem “The Man in the Dump” with the line “Where was it one first heard the truth, the, the.” In essence we’re all kind of picking through the trash bins of history seeking treasures of sorts seeking wisdom and enlightenment at the same time as being immersed in our actual experience with its beauties and its terrors, it’s emotions and it’s thoughts, observations, memories and dreams.

So I’m not really after any kind of purity anymore, maybe I never really was, perhaps more a kind of distillation to something that seems essential in something that is evocative maybe something even that disturbs, provokes, and maybe instills some connection that might initiate a human response.

Point d’Arret, 2019, oil on wood, 27 x 26″Eric Banks(b. 1954 Brooklyn, NY) is a Brooklyn-native and lives and works in Rhinebeck, NY. In 1977, he obtained his B.A. from Queens College of the City University of New York, NY. In 1981 he received his M.F.A. from Maryland Institute College of Art, Hoffberger School of Painting. Banks has been awarded the Pollock-Krasner Foundation Grant, Edward Albee Foundation Grant, and Walters Fellowship. He has exhibited nationally; most-recently, his work has been on view at NYC galleries, such as Amos Eno Gallery and Sideshow Gallery.

-

Hiroyuki Hamada Immigrating from Japan to the Belly of Empire

I had an opportunity to talk about being an immigrant, Japan, our society, politics and so on with Jeff J Brown. I think the interview turned out to be a very good one. I got to talk about making art as well.

Here is an excerpt:

“I think corporal punishment given to school kids when I was growing up in Japan taught me how a hierarchical order can be maintained for the sake of having the order. The resulting order can operate without meeting the needs and desires of subject populations, sort of like schools or prisons. And capitalist society also maintains itself by economic punishment. What’s prominent about an order maintained by fear, threats, violence and so on, is that it forms itself regardless of each individual’s intrinsic connection to self, to others, to communities, to nature and so on. It is a way to form a social structure, but it is also an effective way to detach subject populations from their true human nature. This is a crucial step in commodifying basic human rights to be turned into profit. This is why capitalism is so effective in forming and perpetuating a hierarchical order while dehumanizing the population drastically, without even their knowledge. I think we as a species should be able to do better than that. The survival of our species depends on it, I think.

Also, the art making process has taught me that in order to come up with a profound solution for a given work, one needs a certain amount of humility, ability to observe elements, openness to accept change, willingness to trust, accept unknown elements, patience to learn the systematic mechanism and so on. These conditions often contradict each other, and they push and pull each other in the process, however, the key to grasping a working mechanism is to understand how the elements act according to their intrinsic characters and their guiding rules. They do not come to a profound formation according to the punitive measures of a master mind. I mean, I can just chop up my canvas and sell them as materials, but that would not realize the potential of the elements. So, what I sense is that we need to incorporate that sort of building process in our society, which truly accounts for the needs of the people, in order to go beyond the neo-feudal hierarchy of exploitation and subjugation. The harmonious whole, with its meaningful mechanism to move our beings does not result from an authoritative coercion. Having honest dialogues with facts placed in objective historical contexts can be a good start for us, I believe. As an artist I can feel that there would be profound results waiting for us.”

HIROYUKI HAMADA IMMIGRATING FROM JAPAN TO THE BELLY OF EMPIRE

-

Gorky’s Granddaughter: Hiroyuki Hamada, April 2018

I had a wonderful studio visit by Zachary Keeting and Christopher Joy from Gorky’s Granddaughter a few weeks ago. They captured it nicely for you to see it as well.

-

the lab magazine Interview

In News onHere is a link to an interview with the lab magazine. It went really well. Please check it out!

-

-

An interview with Merve Unsal

In News onRecently, I had an interview with one of the BoltArt.net editors, Merve Unsal.

Unfortunately, BoltArt site is having a server issue right now but Merve has

put up the interview at her site for now: www.merveunsal.comLet’s hope that BoltArt gets back online soon.

2