-

Gorky’s Granddaughter: Hiroyuki Hamada, April 2018

I had a wonderful studio visit by Zachary Keeting and Christopher Joy from Gorky’s Granddaughter a few weeks ago. They captured it nicely for you to see it as well.

-

The Visual Thread

Here are some images from The Visual Thread, a group show curated by Lori Bookstein which commemorates the 50th anniversary of the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown.

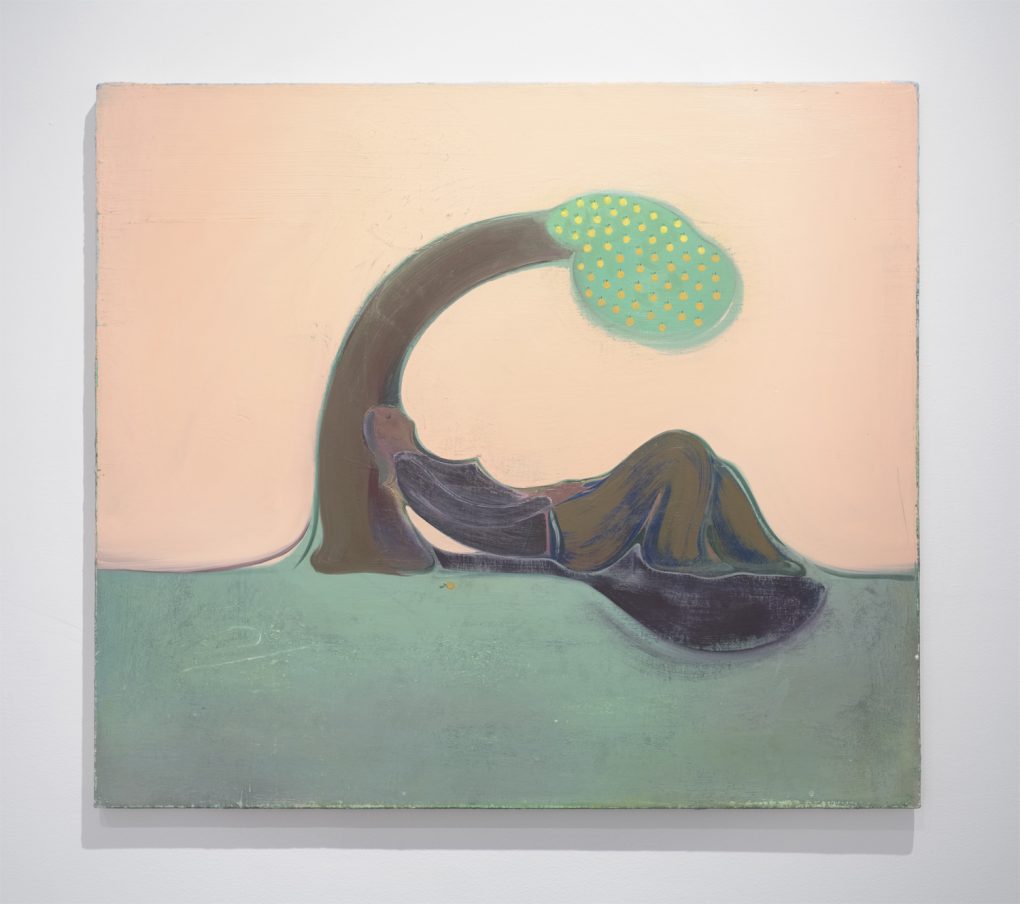

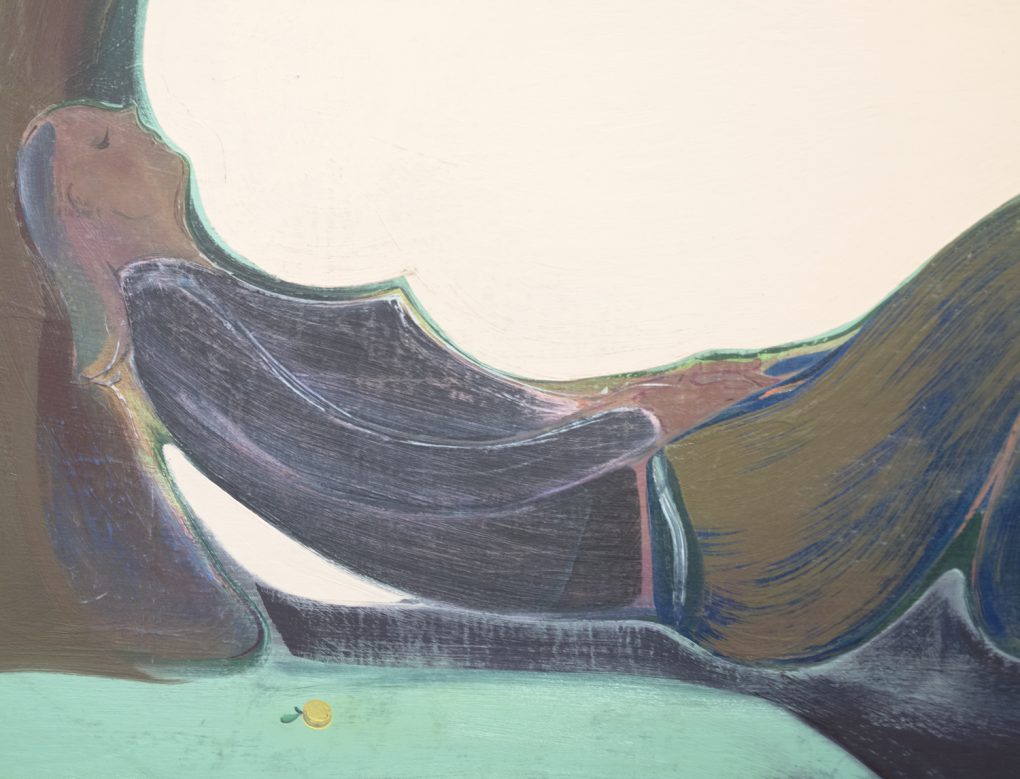

I’m always intrigued by Kate Clark‘s human animal sculptures. And Heidi Hahn is one of my favorite painters. I like how her paintings can be very emotional, yet unmistakably absurd and odd, and all the elements are expressed with a very solid formal visual quality. I am happy to be in the same show with them. My work sits next to Sam Messer’s striking piece titled “how beautiful is the tiger who killed me”.

Well, I can keep talking about other wonderful artists in the show…

Left: Kate Clark, Charmed, 2015, varied materials, 72 x 40x 23 inches

Center: Heidi Hahn, The Body is Not Essential XII, 2016, oil on canvas, 32 x 36 inches

Right: Hiroyuki Hamada, #76, 2011-13, painted resin, 46 x 37 x 31 inches

Left: Hiroyuki Hamada, #76, 2011-13, painted resin, 46 x 37 x 31 inches

Right: Sam Messer, how beautiful is the tiger who killed me, 2017, oil on canvas, 48 x 60 inches

You will probably recognize some of the artists in the show.

#LisaYuskavage#EllenAltfest#RichardBaker#BaileyBobBailey#PaulBowen#MattBollinger#AmyBrener#EllenDriscoll#KateClark#EllenGallagher#HeidiHahn#HiroyukiHamada#SharonHorvath#SamMesser#ElliottHundley#SarahOppenheimer#JenniferPacker#JaniceRedman#JackPierson#JacolbySatterwhite#KahnandSelesnick#DuaneSlick#SableElyseSmith#JamesEverettStanley#TabithaVevers#BertYarboroughYou can see more images here:The show is up till May 20th at Mills Gallery at Boston Center for the Arts. -

200th Birthday of Karl Marx

Repost from my Instagram and Facebook post on 5/6/18:

I’ve always thought artists are somewhat of rebels. We strive to see through seemingly mundane mechanisms of everyday life and come out with a special something that affirms the depth and width of our true condition that goes far beyond the framework forced on us by the establishment.

We stay in our studios and we train ourselves to see how to connect dots and how to grasp the profound flows that lead to a burst of visual language.

Yesterday was the 200th birthday of Karl Marx. He taught us how our society, guided by accumulation of wealth and power, domesticates people in order to harvest humanity as profit. His angle has given us crucial tools to understand our time. Needless to say, as we shift our eyes to outside of our studios, we notice glaring contradictions smoothed out by acrobatic rituals, fear and outright deceptions in culture, economy, politics and so on.

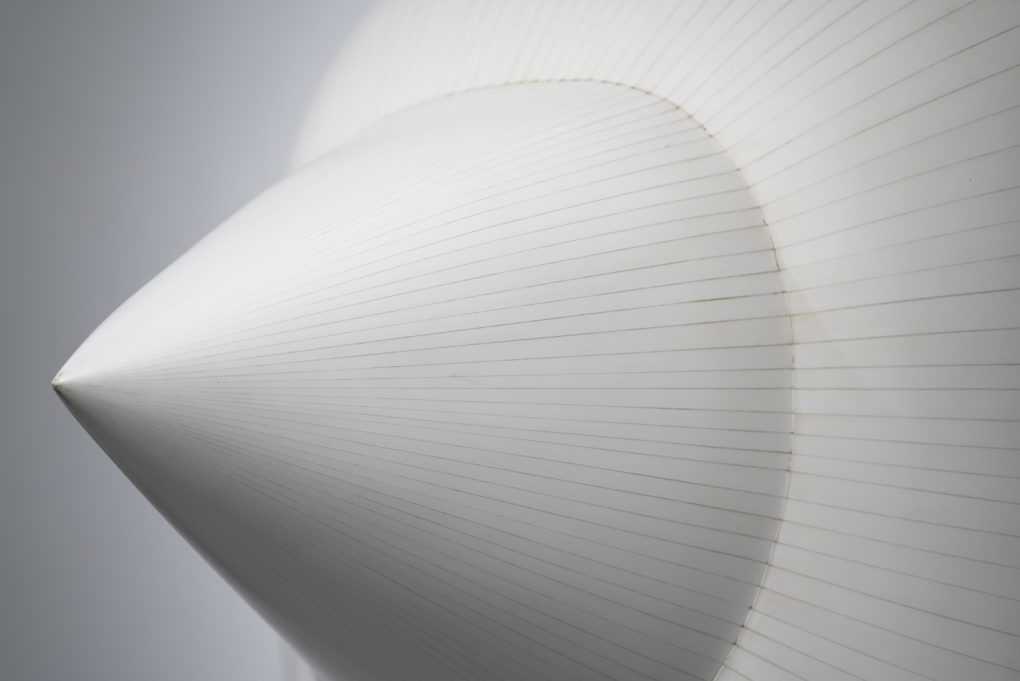

Yesterday, I was in Boston. I stopped at Museum of Fine Arts. Among the mesmerizing exhibits the most stood out was one of Martin Puryear’s pieces. I’ve always liked his work. He has exceptional eyes to focus on that something that speaks to our essential beings in such a profound way.

With the particular piece, I noticed how casual, raw and wild the mode of expression was. There was a playfulness in how he worked with dynamics among elements–the harmony among wood stains, small whimsical wood parts, seemingly random patches of wire meshed surface, chalk markings on wood and so on gave it an unassuming front, but the essential insight was unmistakably expressed as a solid life emanating from the assembly.

When I tried to leave and looked back at the piece, I was struck how transparent the mesh surface was. I could see through to the room behind it. Yet, the ellusiveness and frankness of the expression cleverly emphasized the profoundness of the life with its elusiveness.

A work like that certainly gives us courage to keep going.

I've always thought artists are somewhat of rebels. We strive to see through seemingly mundane mechanisms of everyday life and come out with a special something that affirms the depth and width of our true condition that goes far beyond the framework forced on us by the establishment. We stay in our studios and we train ourselves to see how to connect dots and how to grasp the profound flows that lead to a burst of visual language. Yesterday was the 200th birthday of Karl Marx. He taught us how our society, guided by accumulation of wealth and power, domesticates people in order to harvest humanity as profit. His angle has given us crucial tools to understand our time. Needless to say, as we shift our eyes to outside of our studios, we notice glaring contradictions smoothed out by acrobatic rituals, fear and outright deceptions in culture, economy, politics and so on.Yesterday, I was in Boston. I stopped at Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Among the mesmerizing exhibits the most stood out was one of Martin Puryear's pieces. I've always liked his work. He has exceptional eyes to focus on that something that speaks to our essential beings in such a profound way. With the particular piece, I noticed how casual, raw and wild the mode of expression was. There was a playfulness in how he worked with dynamics among elements–the harmony among wood stains, small whimsical wood parts, seemingly random patches of wire meshed surface, chalk markings on wood and so on gave it an unassuming front, but the essential insight was unmistakably expressed as a solid life emanating from the assembly. When I tried to leave and looked back at the piece, I was struck how transparent the mesh surface was. I could see through to the room behind it. Yet, the ellusiveness and frankness of the expression cleverly emphasized the profoundness of the life with its elusiveness.A work like that certainly gives us courage to keep going.

Posted by Hiroyuki Hamada Art on Sunday, May 6, 2018

-

Guild Hall Show Opens Today

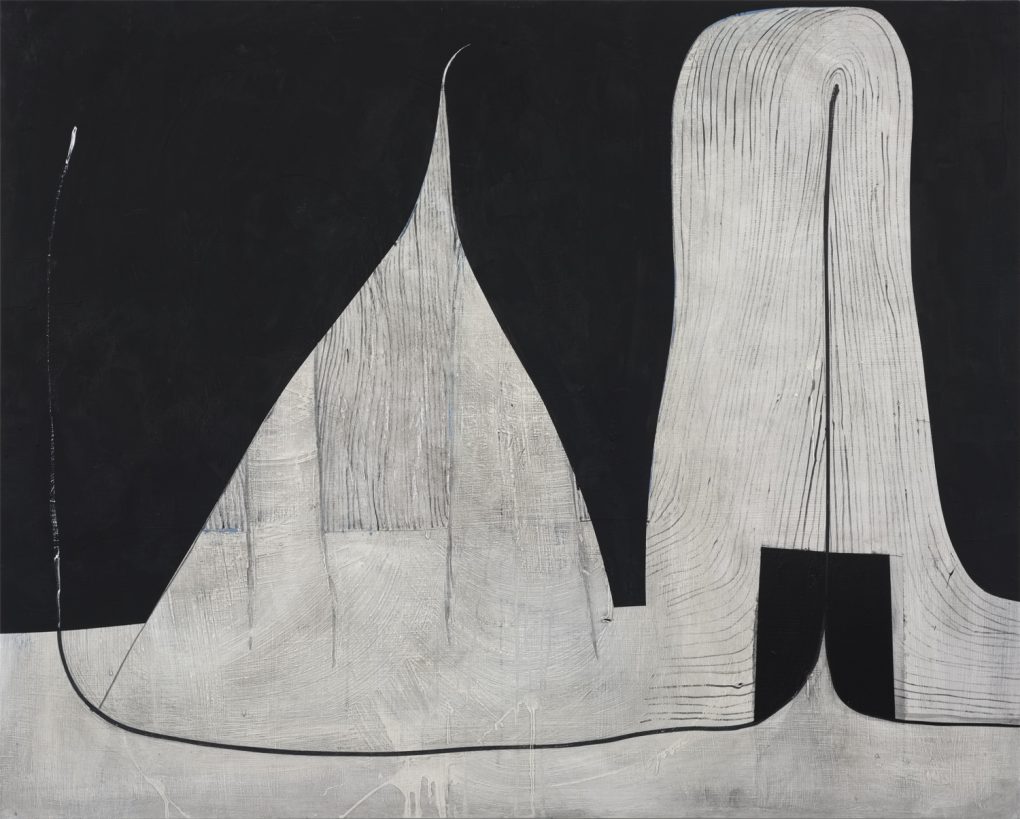

I am very happy about how the show turned out. The new piece (pictured below) was safely brought into the museum. It is surrounded by five of my Piezography prints. Scroll down for some images from the show…

82, 78 x 61 x 26 inches, pigmented resin, 2017-18

82, 78 x 61 x 26 inches, pigmented resin, 2017-18Hiroyuki Hamada: Sculptures and Prints

February 24, 2018 – March 25, 2018

Reception: February 25, 2018, 2:00pm- 4:00pmGallery Talk with Hiroyuki Hamada: March 10, 2018 2:00pm

Guild Hall

Address: 158 Main Street, East Hampton, NY 11937

Phone: 631.324.0806Click to enlarge

-

Laid, Placed, and Arranged: A Panel Discussion at The Phillips Collection

There will be a panel discussion on the show at the University of Maryland Gallery on November 9th. 6:30pm at the Phillips Collection. If you know anyone in the area who might be interested, please let them know.

Event details from the Phillips Collection site: “Join artists Hiroyuki Hamada, Francie Hester, Ellington Robinson, and Wilfredo Valladares, along with exhibition curator and moderator Taras W. Matla, as they discuss their contributions to the exhibition Laid, Placed, and Arranged, on view now through December 8, 2017, at the University of Maryland Art Gallery.

This exhibition and panel discussion is in partnership with The Phillips Collection and its ongoing series Creative Voices DC. Financial support provided by the Dorothy and Nicholas Orem Exhibition Fund and a generous grant from the Maryland State Arts Council.”

-

University of Maryland Art Gallery show

Four of my sculptures and two of my paintings will be in a show at the University of Maryland Art Gallery. There will be a catalog with my interview as well.

I’m looking forward to seeing the new paintings with the sculptures. The show opens on September 6th, 2017 and runs through December 8th, 2017.

Here is the info from the gallery:

“The University of Maryland Art Gallery invites you to an evening reception for Laid, Placed, and Arranged. This exhibition explores recent work made by six University of Maryland MFA alumni — Laurel Farrin, Hiroyuki Hamada, Francie Hester, Meg Mitchell, Ellington Robinson, and Wilfredo Valladares — who have gone on to become significant voices in the realm of contemporary art and academia.

Laid, Placed, and Arranged will be on view September 6-December 8, 2017, and is supported in part by a generous grant from the Maryland State Arts Council. Complimentary table hors d’oeuvres along with a selection of wine, beer, and soft drinks will be served.

Admission is free and open to the public.

Opening Reception

Wednesday, September 6, 2017, 5:00 p.m. to 7:00 p.m.Location

University of Maryland Art Gallery

1202 Parren J. Mitchell Art-Sociology Bldg.Parking

After 4:00 p.m. parking is free in Lots JJ2, JJ3, and 1b.

(At the intersection of Mowatt Lane and Campus Drive.)Also On View

A series of smaller exhibitions — some rotating, others permanent — round out the visitor experience at the Gallery. Make sure to check out In Memoriam: Andy Dunnill and Recent Gifts.” -

Good Bye to Bill King

I’ve been feeling numb and broken over the passing of my friend Bill King.

The objective reality is that he was a rare human who defied the absurdity and cruelty of our time by relentlessly motivating us to see what we are through playfulness, mystery, wonder, warmth, fragility and strength in his work. He proved to us that it is indeed possible to live with dignity and humanity even in a time like ours. He was 90 years old. Knowing how he was, he probably worked till the very end. Ending of his life should be celebrated as a great achievement.

But I selfishly wish that he still calls me to say hi, that we still exchange studio visits and chat about how things are.

Not feeling like saying good bye to him at all.

Bill, where did you go?

0