-

New additions to the site, December 14, 2022

I asked my wife what I should write to go with this post. She jokingly said that I should write about why I make such weird images. I don’t know the answer to be honest. But I think things are weird. We stay in our routines, we observe rules, ideas, myths and beliefs flooding out of big corporate entities to remain “good citizens” of “democratic countries”. But when we take one step outside and look in, we see people hurting each other for nothing, people following ridiculous rules and people being forced to play clowns in a circus only to keep up with the status quo. People pay prices to stay in these invisible cages. The cages distort the bodies, the faces, the minds and the souls. The rosy promises and slogans are conditional, propping up the hierarchy governed by money and violence. Weird to see things upside down. Weird to see people sleeping on streets when rich people have many houses. Weird to see more money spent on bombs than healthcare, housing, and food for the people. Needless to say these things aren’t just weird, they are brutal and upsetting. So there is that. But when I work, I try to empty my head to feel visual elements for what they are, and let them speak; surely weird things come out, but profoundly fascinating things happen among them too, just as in real life. Perhaps it is a practice to find potentials among elements when they can interact on their own accord. Maybe they are like how life can be. Anyway, I’m posting because I just added 6 recent paintings of mine to my site. They are under Painting. You can see multiple views and details for each piece.

Studio update:

I’ve been working on new sculptures. The next set of pieces will be sculptures. -

everything is free now

In Art, Artist, Capitalism, colonialism, Culture, digitalization, empire, Exhibition, financialization, imperialism, News, outdoor art, Painting, public art, street art onI had a great time strolling around Brooklyn with Josh and David from everythingisfreenow.org a few days ago. It’s been awhile since everythingisfreenow.org left social media platforms. But of course that doesn’t mean they don’t exist. They’ve quietly placed hundreds of paintings on the streets of Brooklyn so far. If you know where to look, you see that their work has become a part of the cityscape. Their work has turned the public space into a place to appreciate and discuss art and life.

The language of art manifests as the language of life. No matter how hard the ruling class tries to digitize everything, financialize everything, commodify everything, colonize everything to mold everything into the imperial framework, life finds ways to build its social fabric on its own terms.

New York has gone through so much: Wave after wave of neoliberal restructuring have been inflicted in the name of fighting crimes, terrorisms, and the virus. The same people who define “crises” have been the ones who benefit from “the solutions”. The social hierarchy is maintained and continues to function as a machine of structural extortion. But life still persists as art on streets, community gardens, cooperative housing projects and etc. Seeing them up close and hearing about them from Josh and David warmed my heart.

Here are some photos from their website:

-

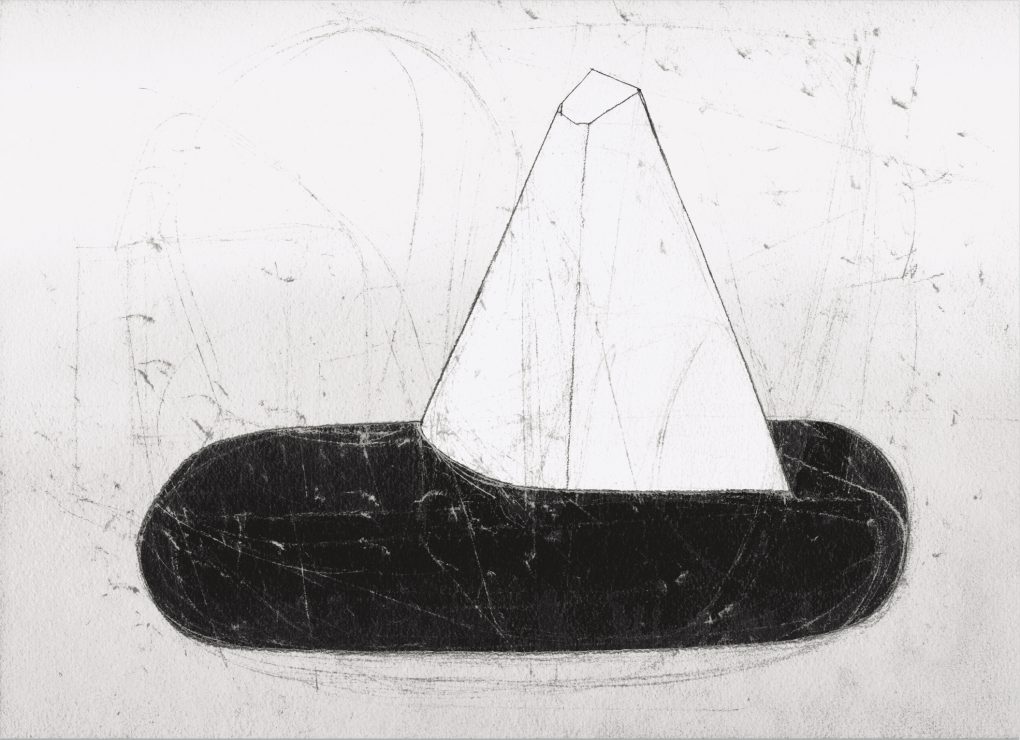

New Print B18-03

I was so frustrated with this one that when I finished it the sense of relief overwhelmed my sense of accomplishment. But it’s always profound to capture something indescribable speaking so decisively. Practicing art making gives us courage to face the unknown, embrace it and appreciate it. If there is truly an essential meaning in “art education”, that’s what we can offer—to see the world for what it is, with the unknown, complexity, bigger dynamics, smaller dynamics, layers, interconnectedness and all to be constructive. Such an angle helps us to be a part of harmony for all, instead of a part of exploitation and subjugation for few.

-

Where do we stand to stand for humanity?

The image of French children with their hands behind their heads kneeling before heavily armed military police compellingly signifies the mechanism of capitalism.

Children are our future. Their courageous burst of humanity against injustice, exploitation and subjugation is a bright hope of our future. The system brutally mutilates it off of children with a sheer force of violence as they push them into an imperial cage of corporatism, colonialism and militarism.

The savagery of this act signifies the whole scheme as a domestication of humanity in harvesting profits off of the people.

The global capitalist hierarchy of brutality is facing itself as it relies on fear to maintain “democracy”, “freedom” and “humanity” within the cage. They were once head-chopping colonizers in Algeria. They destroyed Libya in a brutal armed robbery, massacring countless innocent people. As they fail to destroy Syria, the self-destructive momentum of contradictions and hypocrisy viciously assaults its own people.

We the artist face the dilemma of expressing what it is to be humans while firmly being stuck in the framework of corporatism, colonialism and militarism. We all struggle to find our own balance to stand in this precarious time. For all of you who struggle, I would like to say that you are not alone and I thank you for your struggle.

-

1500 Rakan Statues of Mount Nokogiri

People sometimes ask me what religion Japanese people practice. I usually end up saying that Japanese people aren’t very religious at all. But paradoxically, if you go to Japan, you encounter huge shrines at tourists’ spots and there are numerous smaller ones across the country in many forms. You visit a Japanese household, you might also find a shrine, a box shaped prayer spot, called butsudan.

There certainly are indications that Japanese society is bound together, to a certain extent, with beliefs, values and norms deriving from variations of Buddhism and Shintoism.

To me, who grew up in Japan, it is natural to perceive such a traditional framework as a cohesive layer that can be loosely described as sort of “religious”. It guides traditional ceremonies and rituals of life, death and spiritual, and it contributes to world views of the Japanese people in varying degrees.

However, it should also be noted that this framework really does not address fundamental existential questions for the Japanese people today. In other words, people would go along with the customary rituals as long as they facilitate their social interactions and obligations, however, as soon as they impede their material necessity, they can be set aside. Japanese society is extremely secular and the grip of the socioeconomic hierarchy over its people is very firm. After all, Japan has played a crucial role as an economic power in the western hegemony for generations after it was incorporated into the order of the American empire.

Our trip to Mount Nokogiri, however, has shown me how the abstract notion of traditional Japan has many layers that are deeply conflicting and it has had tumultuous aspects as we examine it in historical contexts.

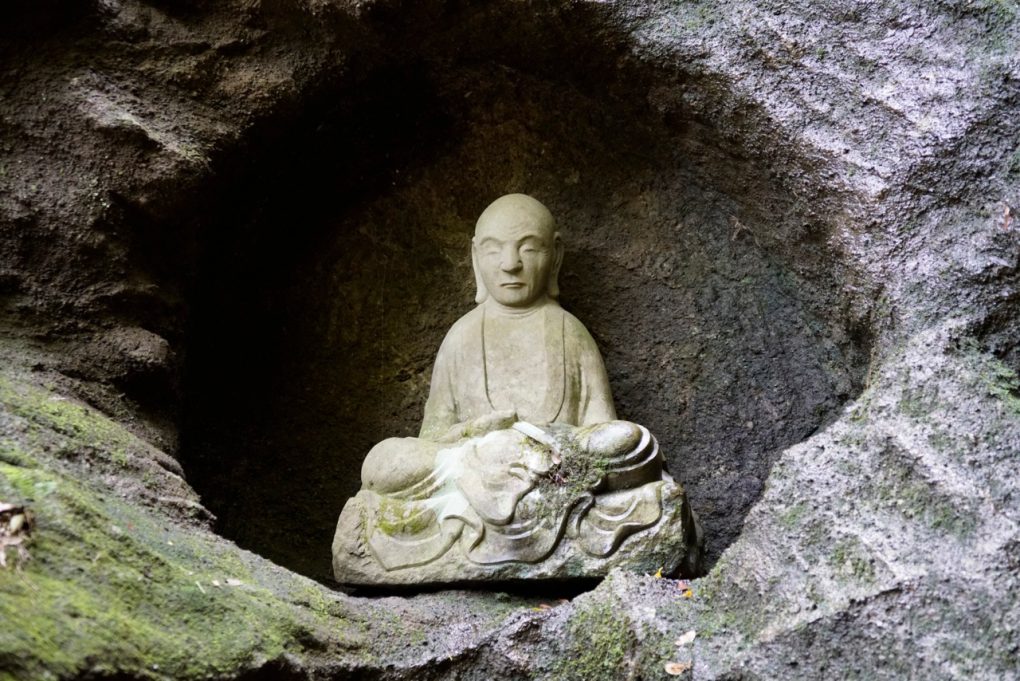

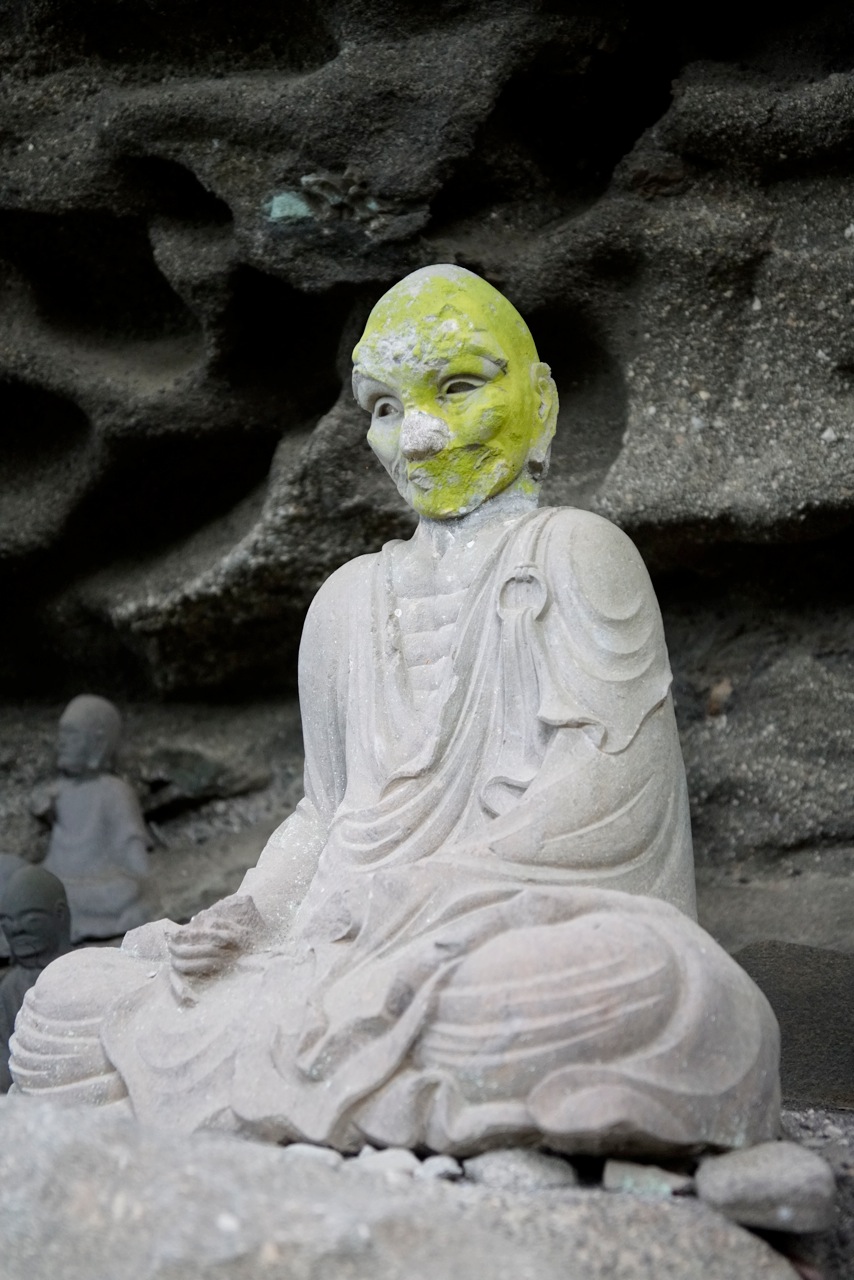

Mount Nokogiri is located in Boso Peninsula, Chiba. As you can see on a map it is relatively close to Tokyo. My wife and I visited the area once before we had our kids. I loved seeing rakan statues (stone carved arhat statues) along the path during our hike. To me they appeared as expressions of lives emanating from the area which had been regarded as sacred for many centuries.

This time, we decided to stay for a couple of nights at a nearby seaside city, Tateyama. The inn we picked had a nice view of the water and hot spring baths. Since my mother couldn’t take the mountain hike, I wanted her stay to be nice as well. It was a few rustic train stops away to Mount Nokogiri.

I really liked riding the rural trains in the area. Going a few hours south from Yachiyo city into the Peninsula made the scenery much greener and it was fascinating to observe a glimpse of country life as we passed fields cultivated with various crops, a house sitting among trees without a discernible way to get there, huge hawks flying over us and the water visibly getting cleaner as we got closer to our destination.

The hike was magnificently wonderful. It was a bit strenuous for me, with numerous steps. But I’ve never felt a physical exercise to be so refreshing, so invigorating and so satisfying (in fact, it inspired me to start exercising again when I came back to the States).

Nokogiri means saw blade. The jagged appearance of the mountain stems from its history being a prominent stone quarry.

I took many pictures of the small statues as we walked. If you look at the statues carefully, you will notice that the necks of them have traces of reattachment. Those statues were all violently destroyed once during the haibutsukishaku movement. As the rule of the Tokugawa shogun family ended in 1868, the new government, aspiring to be one of the imperial powers of the time, embarked on drastic reforms. One of them was a separation of Buddhism and Shintoism. Shintoism was elevated as a national religion while Buddhism was regarded as a part of the old power. There was a strong momentum to see the power of Buddhist entities as an abusive and corrupt part of the past. The accounts from the time certainly indicate that the deeds of the Buddhist class did reflect such descriptions. The result was an emergence of a large scale destructive movement across the country against anything Buddhist. As to Shintoism, it eventually ended up as the backbone of imperial Japan, propping up the Japanese emperor as a living god, prompting a direct collision with the US imperial plan over the hegemonic rule of Asia. The inhumane momentum of destruction and atrocity took many lives in Asian countries. In the name of the living god the Japanese colonizers sent young lives as suicide bombers. The colonizers of the US dropped nuclear bombs on two cities full of people in order to declare its hegemonic superiority against enemies and allies alike.

Today the Buddihist legacy in the Mount Nokogiri area is regarded as a significant cultural asset. The beautiful trails are well maintained, so are the shrines and statues for many visitors. It was breathtaking to encounter spectacular views throughout our walk. The weight of the historical layers also compounded the profound orchestration of the natural elements. The moss covered expressions of the aged statues–sad, tormented, resigned, angered, struggling, peaceful and fulfilled–were voices from the past beautifully sublimated within the harmony of nature and people.

As we were waiting for our bus back home, a man at a tiny local restaurant insisted that we take a look at an underground imperial Japanese fortress in Tateyama. Although we couldn’t extend our trip for it, according to him, a mile-long tunnel dug during WW2 is something you must not miss if you were in the area. He also mentioned that the entire Mount Nokogiri was a huge military fortress during the war. To the imperial Japan, the area, situated at the entrance to Tokyo Bay, was the last defense on the ground protecting Tokyo against the invading US forces.

Famed sculptor Isamu Noguchi said that time can heal stones in describing his stone carving process. Time can certainly give us a thrust of objectivity while natural elements can provide a layer of harmony, presenting a new way to understand what unfolds before us. Mount Nokogiri certainly stood as a sacred ground before me. The overwhelming sense of awe generously erased the scars of human atrocity.

However, it has also made me aware of myself as a captive of our time. Tateyama’s imperial Japanese base is now a base for the Japanese self-defense force. The corporate media is eerily silent about the fortification of islands around Okinawa, which lies at the tip of the archipelago and houses an American military base. Japanese regulations have been changed to allow a Japanese “self-defense force,” ostensibly to operate as a part of the western force against China. Those shifts coincide with the US pacific policy to counter China as an emerging economic power. And more urgently, I couldn’t help being reminded of inhumane atrocities of our time–bombing campaign against people, suicide bombing, underground fortress, destruction of environment and cultural heritage and so on and so forth are all elements emerging from the western colonial wars being waged against the Middle East and elsewhere today.

Have we learned anything from the past? Our ability to see our history and events embedded in it, weaving the flow of time and space, as a unified front, as a collective part of our identity, allow us to tolerate pains of atrocity, allow us to reconcile, allow us to rebuild and allow us to be. But we do know that the significant portions of the sufferings and deaths are endured by those who are powerless. How could we allow ourselves to let the momentum of time swallow so many of our fellow humans? Why are we tolerating colonial destabilization of “other people’s”? How could we close our eyes as we encounter people sleeping on streets or losing their lives because they can’t afford to be healthy? Why can’t we focus our hope for renewal for the people who have and will suffer the most? How could we recognize the fact that our willingness to tolerate the hierarchy of money and violence, as the shape of our species, inflicts pain against “others” and against ourselves at the same time, forcing ourselves to expect nuclear missile attacks instead of reaching out for sharing and peace?

Every time I hear people say that for things to get better, things have to get much worse, I think of what happened in Fukushima. Three nuclear meltdowns have not woken up the people. The nuclear industrial complex of Japan is firmly embedded within the war economy of the empire.

This is not the time for conflict. This is the time we need each other to see what has become of us. Let there be braveness, determination and steadfastness in renouncing the cannibalistic momentum of self-destruction. The sacred power of nature will always embrace us no matter how we will do.

-

Hiroyuki Hamada Immigrating from Japan to the Belly of Empire

I had an opportunity to talk about being an immigrant, Japan, our society, politics and so on with Jeff J Brown. I think the interview turned out to be a very good one. I got to talk about making art as well.

Here is an excerpt:

“I think corporal punishment given to school kids when I was growing up in Japan taught me how a hierarchical order can be maintained for the sake of having the order. The resulting order can operate without meeting the needs and desires of subject populations, sort of like schools or prisons. And capitalist society also maintains itself by economic punishment. What’s prominent about an order maintained by fear, threats, violence and so on, is that it forms itself regardless of each individual’s intrinsic connection to self, to others, to communities, to nature and so on. It is a way to form a social structure, but it is also an effective way to detach subject populations from their true human nature. This is a crucial step in commodifying basic human rights to be turned into profit. This is why capitalism is so effective in forming and perpetuating a hierarchical order while dehumanizing the population drastically, without even their knowledge. I think we as a species should be able to do better than that. The survival of our species depends on it, I think.

Also, the art making process has taught me that in order to come up with a profound solution for a given work, one needs a certain amount of humility, ability to observe elements, openness to accept change, willingness to trust, accept unknown elements, patience to learn the systematic mechanism and so on. These conditions often contradict each other, and they push and pull each other in the process, however, the key to grasping a working mechanism is to understand how the elements act according to their intrinsic characters and their guiding rules. They do not come to a profound formation according to the punitive measures of a master mind. I mean, I can just chop up my canvas and sell them as materials, but that would not realize the potential of the elements. So, what I sense is that we need to incorporate that sort of building process in our society, which truly accounts for the needs of the people, in order to go beyond the neo-feudal hierarchy of exploitation and subjugation. The harmonious whole, with its meaningful mechanism to move our beings does not result from an authoritative coercion. Having honest dialogues with facts placed in objective historical contexts can be a good start for us, I believe. As an artist I can feel that there would be profound results waiting for us.”

HIROYUKI HAMADA IMMIGRATING FROM JAPAN TO THE BELLY OF EMPIRE