-

The Visual Thread

Here are some images from The Visual Thread, a group show curated by Lori Bookstein which commemorates the 50th anniversary of the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown.

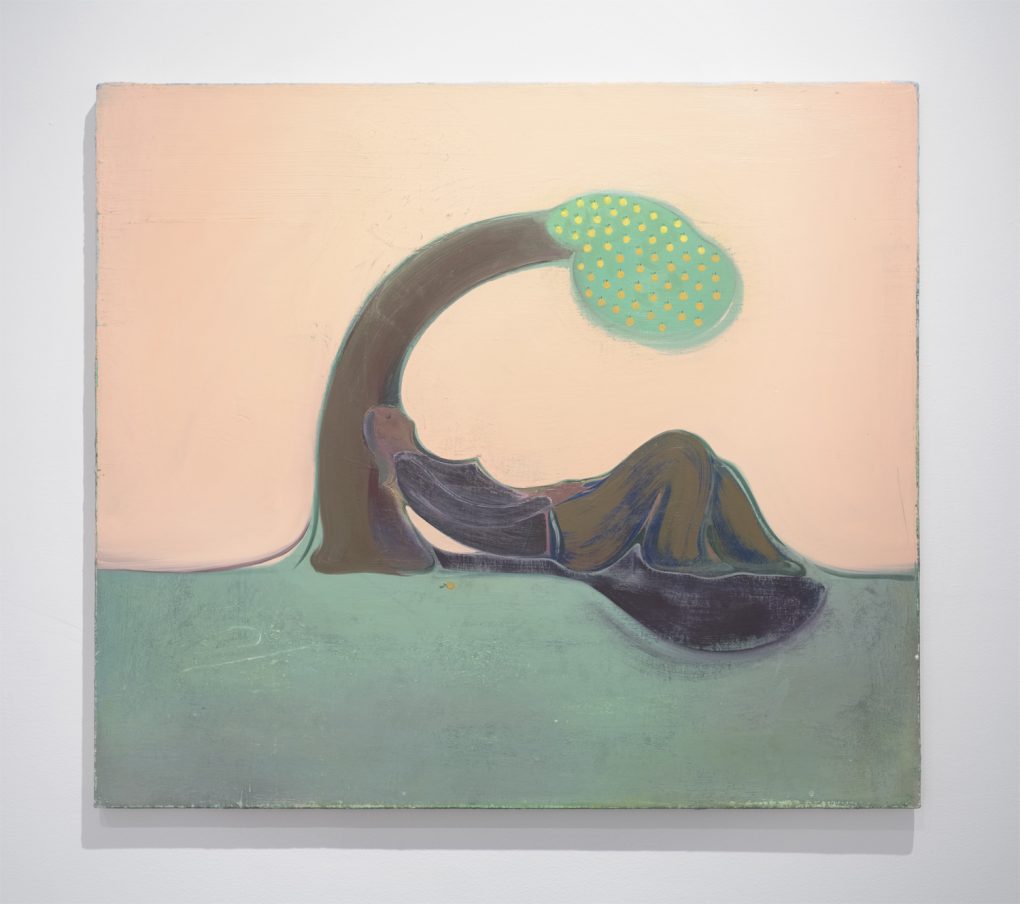

I’m always intrigued by Kate Clark‘s human animal sculptures. And Heidi Hahn is one of my favorite painters. I like how her paintings can be very emotional, yet unmistakably absurd and odd, and all the elements are expressed with a very solid formal visual quality. I am happy to be in the same show with them. My work sits next to Sam Messer’s striking piece titled “how beautiful is the tiger who killed me”.

Well, I can keep talking about other wonderful artists in the show…

Left: Kate Clark, Charmed, 2015, varied materials, 72 x 40x 23 inches

Center: Heidi Hahn, The Body is Not Essential XII, 2016, oil on canvas, 32 x 36 inches

Right: Hiroyuki Hamada, #76, 2011-13, painted resin, 46 x 37 x 31 inches

Left: Hiroyuki Hamada, #76, 2011-13, painted resin, 46 x 37 x 31 inches

Right: Sam Messer, how beautiful is the tiger who killed me, 2017, oil on canvas, 48 x 60 inches

You will probably recognize some of the artists in the show.

#LisaYuskavage#EllenAltfest#RichardBaker#BaileyBobBailey#PaulBowen#MattBollinger#AmyBrener#EllenDriscoll#KateClark#EllenGallagher#HeidiHahn#HiroyukiHamada#SharonHorvath#SamMesser#ElliottHundley#SarahOppenheimer#JenniferPacker#JaniceRedman#JackPierson#JacolbySatterwhite#KahnandSelesnick#DuaneSlick#SableElyseSmith#JamesEverettStanley#TabithaVevers#BertYarboroughYou can see more images here:The show is up till May 20th at Mills Gallery at Boston Center for the Arts. -

What Do We the Artists do?

I made this piece around the year 2000. Things were much simpler for me back then. The only thing that guided me was the momentum of my studio practice–like an explorer, I searched, was mesmerized and was content with newly found visual-scapes. The world–the human world–seemed like an extension of the great oceans and lands with its harmony and order. If I did have to justify my motive, perhaps I felt responsible for the path that saved my life from self-destructive anger and sadness. I didn’t feel the responsibilities arising from being a parent, a grown-up, an artist and a human back then. But the pain of life that squeezed my young self never really went away.

What it is to live? When one decides to be a constructive force for our species, for our fellow creatures and for the environment, what can artists do? When our efforts are harvested to decorate power and authority, and when our efforts are used as currency to protect the hierarchy of money and violence, how do we assert our roles to be human and to show what it is to be human?

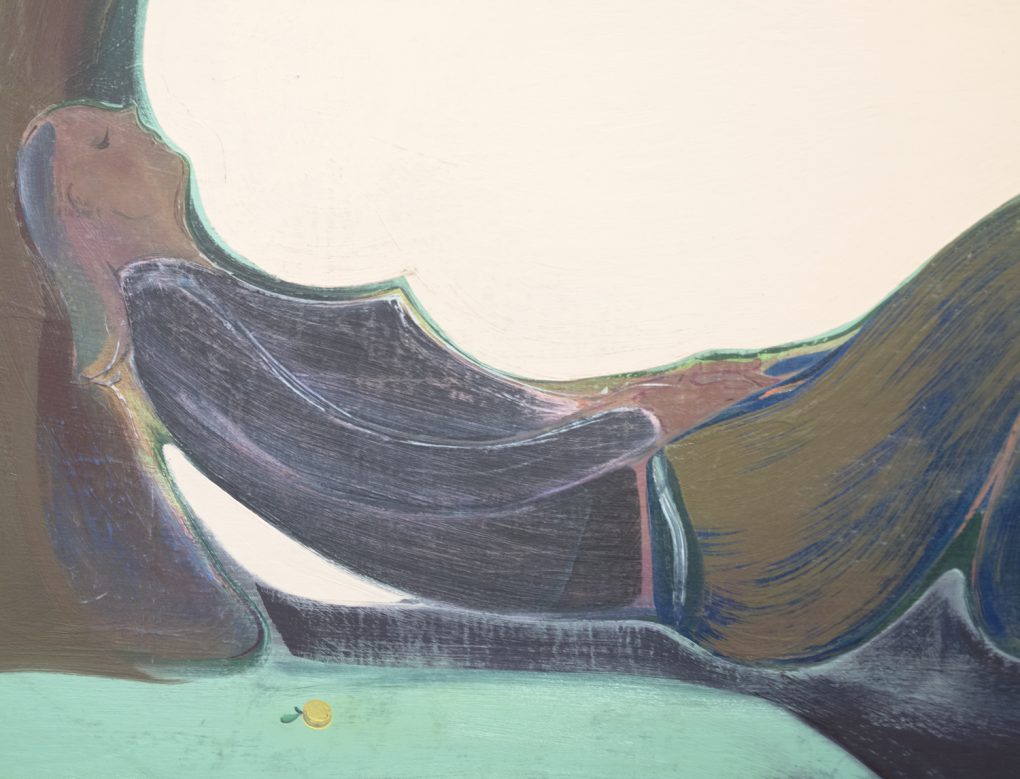

Getting back to the piece, shortly after it was made, I gave it to my wife in exchange for her grandmother’s ring, which she loved. In turn, I gave the ring to her as a wedding ring. The piece has been put away for a while, but my wife wanted to see it next to one of my new pieces, so here they are.

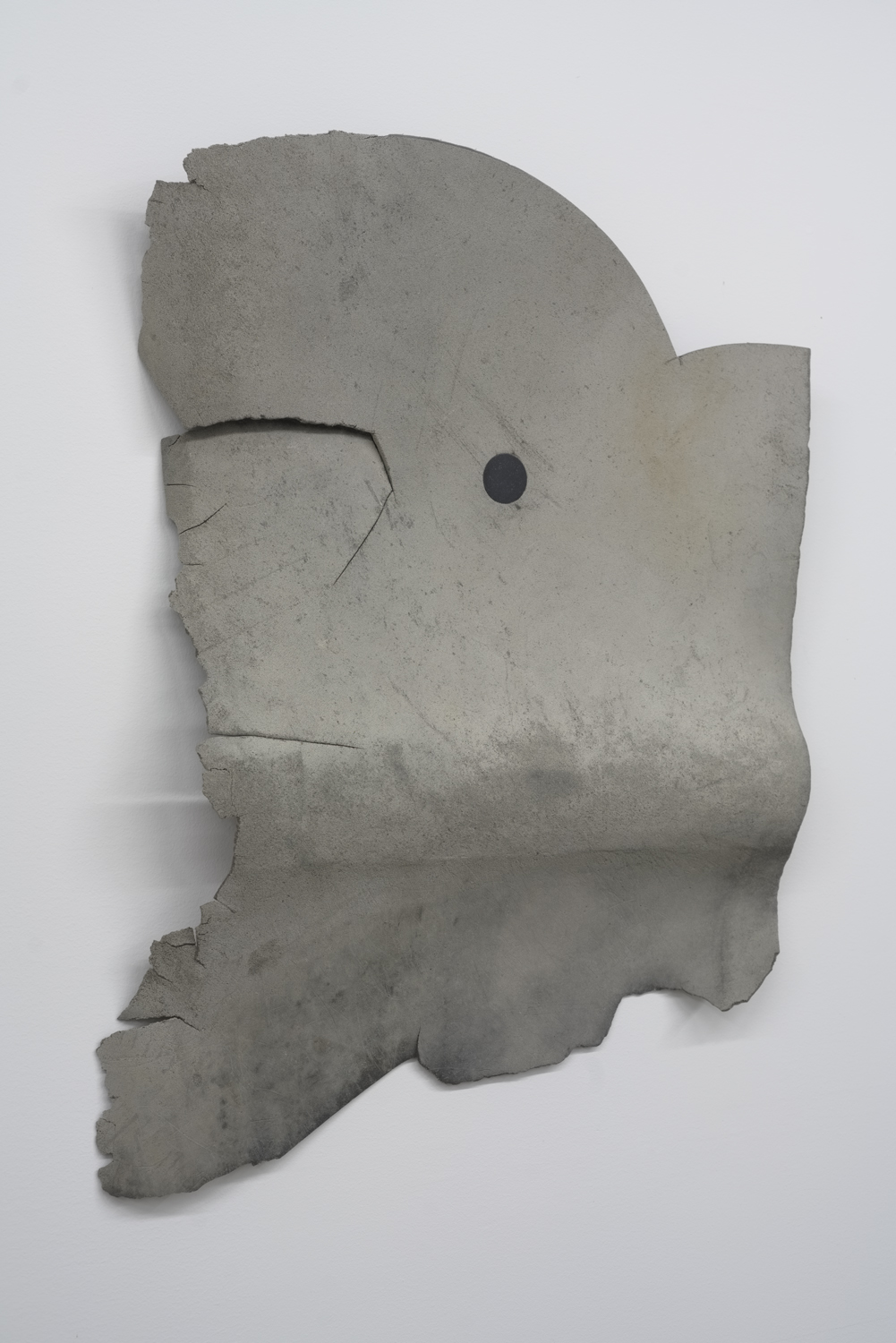

#83, 33 x 24 x 3 inches, found object and resin, 2014-18

#30, 18″ diameter x 8″, enamel, plaster, resin, tar and wax, 2000

-

New Sculpture #83

Our visual perception relies heavily on inputs from our brains. Our eyes are physically a part of the brains from their proximity and connections. Our memories, expectations, preconceptions and so on play big roles in making us see what we see. In a long stretch of studio practice we cultivate our own trajectories filled with those filters which can push us forward while also potentially preventing us from seeing other things. Sometimes our eyes guide us to imagine how the piece can turn out. Sometimes they prevent us from seeing an obvious until we can face it constructively. In the process, the time and space bend each other and allow us to experience the essence of our being stretching beyond the framework of corporatism, colonialism and militarism.

This piece took a few years to finish, but I’m finally done with it.

-

Guild Hall Show Opens Today

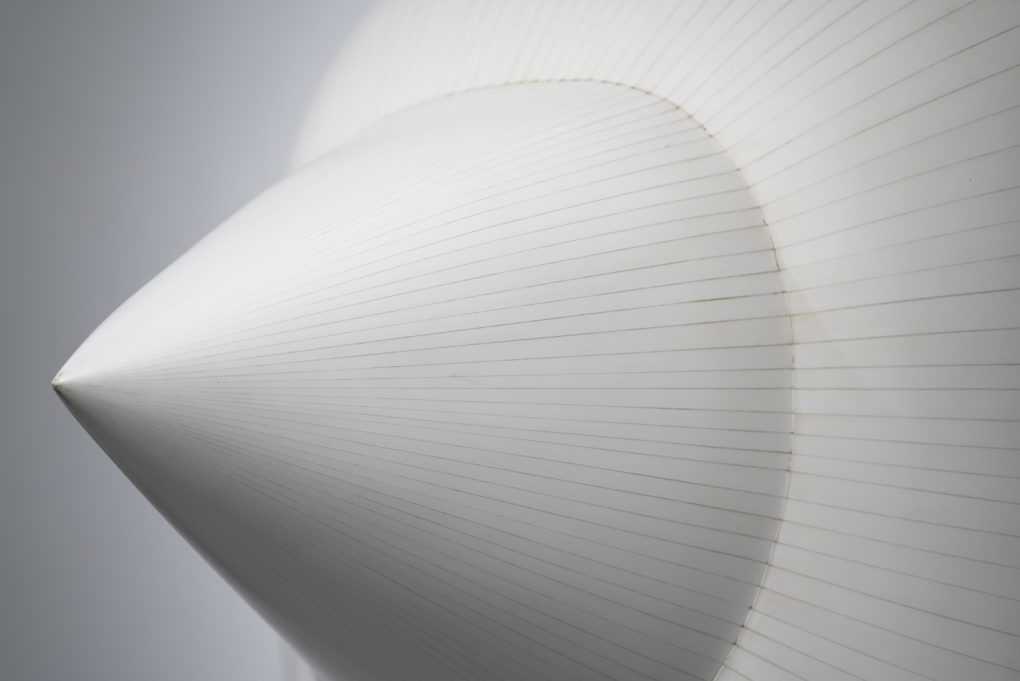

I am very happy about how the show turned out. The new piece (pictured below) was safely brought into the museum. It is surrounded by five of my Piezography prints. Scroll down for some images from the show…

82, 78 x 61 x 26 inches, pigmented resin, 2017-18

82, 78 x 61 x 26 inches, pigmented resin, 2017-18Hiroyuki Hamada: Sculptures and Prints

February 24, 2018 – March 25, 2018

Reception: February 25, 2018, 2:00pm- 4:00pmGallery Talk with Hiroyuki Hamada: March 10, 2018 2:00pm

Guild Hall

Address: 158 Main Street, East Hampton, NY 11937

Phone: 631.324.0806Click to enlarge

-

University of Maryland Art Gallery show

Four of my sculptures and two of my paintings will be in a show at the University of Maryland Art Gallery. There will be a catalog with my interview as well.

I’m looking forward to seeing the new paintings with the sculptures. The show opens on September 6th, 2017 and runs through December 8th, 2017.

Here is the info from the gallery:

“The University of Maryland Art Gallery invites you to an evening reception for Laid, Placed, and Arranged. This exhibition explores recent work made by six University of Maryland MFA alumni — Laurel Farrin, Hiroyuki Hamada, Francie Hester, Meg Mitchell, Ellington Robinson, and Wilfredo Valladares — who have gone on to become significant voices in the realm of contemporary art and academia.

Laid, Placed, and Arranged will be on view September 6-December 8, 2017, and is supported in part by a generous grant from the Maryland State Arts Council. Complimentary table hors d’oeuvres along with a selection of wine, beer, and soft drinks will be served.

Admission is free and open to the public.

Opening Reception

Wednesday, September 6, 2017, 5:00 p.m. to 7:00 p.m.Location

University of Maryland Art Gallery

1202 Parren J. Mitchell Art-Sociology Bldg.Parking

After 4:00 p.m. parking is free in Lots JJ2, JJ3, and 1b.

(At the intersection of Mowatt Lane and Campus Drive.)Also On View

A series of smaller exhibitions — some rotating, others permanent — round out the visitor experience at the Gallery. Make sure to check out In Memoriam: Andy Dunnill and Recent Gifts.” -

Tokyo Underground Cardboard Village Paintings

This story really moved me. It happened in the 90s in Japan. The economic bubble of the 80s had burst and the corporate oriented restructuring and austerity measures gave some people a newly found reality of surviving outside of the corporate routines. The underground station of Shinjuku, Tokyo was filled with cardboard houses populated by the homeless people.

It’s a story of young artists who themselves lived on the edge of the corporate cage, relentlessly trying to be true to humanity…

I came across their website recently and the English translation was missing in the descriptions of their art works which are crucial in telling the story of those artists. I offered to translate some of them and here is a first set of images which tells about how they got started.

Photos are by Naoko Sakokawa.

By Take Junichiro and Takewo Yoshizaki Location: the west exit underground plaza (map)

The very first Shinjuku Underground Station West exit Cardboard painting.

Initially, I wasn’t intending on painting those cardboard houses at the underground corridors at all. I was set to street-paint in Shinjuku, guerrilla style. I walked around Shinjuku with paint cans with “TAKEWO”. But the seemingly open, unrestricted big city didn’t have any place for the guerrilla paint job. We looked and looked but it was all systematic. We just walked around aimlessly with disappointment.

We just stood around hopelessly. The city was gigantic and oppressive. As we followed the river of people in despair, we came across the village of cardboard houses at the Shinjuku Underground Station West Exit. We stumbled onto one of them, knocking the cardboard door:

“What do you want?” A large man with a menacing face answered.

“I’m an artist and I would like to paint on your cardboard house,” I answered.

“Say what??”

“Like I said, I would like to paint on your cardboard house.”

“What!”

“…”

“OK, go ahead.”

That’s how our cardboard house painting got started. We, “TAKEWO” and I, spent all night painting two of the cardboard houses that night. We kept hearing distant sounds of people screaming and shattering glass, and the underground corridor was filled with the police siren and the ambulance siren every once in a while.

In the summer night, our rebellion was born in the underground of the mega city.

http://cardboard-house-painting.jp/mt/archives/2004/09/post_118.php

By Take Junichiro, Takewo Yoshizaki and Yasuhiro Yamane Location: the west exit underground plaza (map)This piece is considered a representative work of ours that survived the forced removal of homeless people by the city of Tokyo on 1/24/1996. It’s THE Shinjuku Underground Station West Exit cardboard house painting.

Yamane mentioned the words “Left Eye of Shinjuku”. The image of those words got the three of us started. It was an all night live painting. The battle of us three. It was so intense that we drew some audience.

Across from the West Exit rotary there is a monument called “An Eye of Shinjuku”. It’s the right eye. And the one we painted is the left one. Makes sense. It’s the pair. The giant eyes had emerged in the Shinjuku underground corridor. The underground became a creature with a soul, baring its teeth against fucking Japan.

Just in case, I must say that the “Left” of “The Left Eye of Shinjuku” has nothing to do with the left wing. So those middle aged dick-wad lefties dragging around the 60s shouldn’t mix this up with that. We are not piece of shit like you all. By the way, it’s odd but when we finished painting this one, we somehow felt that when this painting is gone, that’ll be the time this village will be gone.

The Left Eye of Shinjuku which survived the forced removal had prevailed as a symbol of the underground kingdom.

Then the big fire of February of 1998 came. Soaked in water, the painting was disposed of by the City of Tokyo, and the village has disappeared as well. The Left Eye of Shinjuku really died with the cardboard village.

http://cardboard-house-painting.jp/mt/archives/2004/09/post_117.php

By Take Junichiro Location: the west exit underground plaza (map)A piece made with circles.

I wished my work to be weirdly “inevitable” to the time and the space, not to be about my personal ideology, my philosophy or my process.

I drew lots of circles. A circle doesn’t have edges. It’s round, and it looks the same from any angle. And it’s somewhat humorous. I was edgy but I drew lots of circles.

When we become excessive, we lose the essence. I also wanted my expression to include a healthy dose of looseness and a sense of humor. But that was pretty tough. We often ended up painting with a grabbing-someone-by-the-neck sort of an attitude.

Myself screaming savagely with a knife in my hand, myself being inclusive with a sense of humor, many thoughts went through my mind.

But I felt that the experience which transformed me positively the most is when I touched the warmth of humanity.

http://cardboard-house-painting.jp/mt/archives/2004/09/post_110.php

By Take Junichiro Location: the west exit underground plaza (map)This might be a picture when the cardboard village was being removed.

Far into the picture there is the word “sin” (罪) and to the left, there is the word “no”(無), the piece reads “innocent”(無罪). It was a piece done as a reaction to the not guilty verdict of 1/24/1996 to an activist for protesting against the removal of the cardboard village. Later the verdict was reversed. The activist became the sinner and the city committed a sin of eradicating the cardboard village. A sin is manufactured according to the convenience of the society. The society is made up with individuals. While we fight among each other, we are harming the planet. It might be correct that we are all born sinners.

http://cardboard-house-painting.jp/mt/archives/2004/09/post_104.php

You can see rest of the 121 paintings at their site. And here is the introduction to the work by Take Junichiro.

-

NYC Show Opens This Week

Please join us for the opening reception on Thursday 10/10/13 6-8pm at Lori Bookstein Fine Art.

#73, 2011-13, painted resin, 46 x 70 x 25 inches

#73, 2011-13, painted resin, 46 x 70 x 25 inches

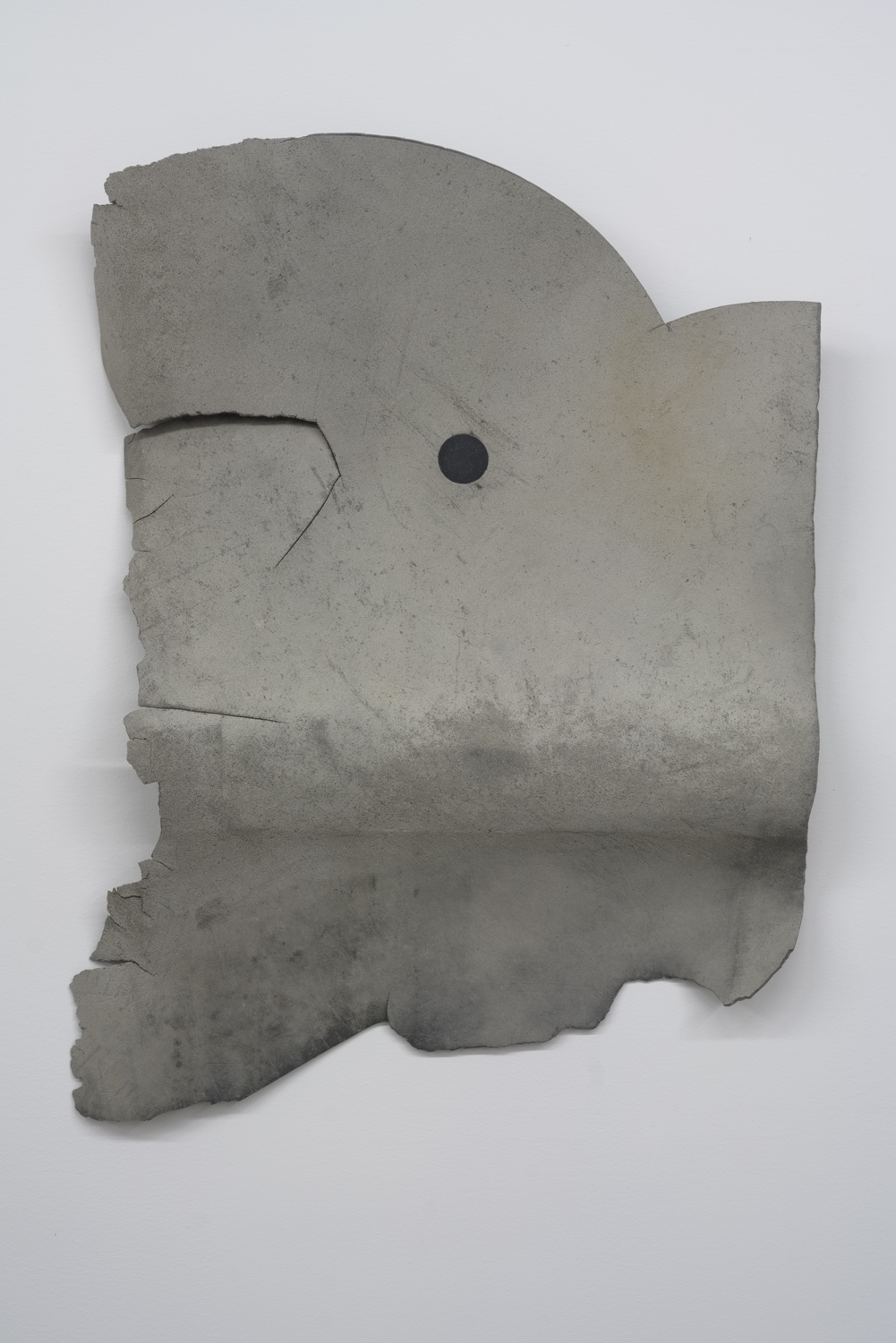

#76, , 2010-13, painted resin, 46 x 37 x 31 inchesLori Bookstein Press release

Hiroyuki Hamada

October 10 – November 9, 2013

Lori Bookstein Fine Art is pleased to announce an exhibition of recent work by Hiroyuki Hamada. This is the artist’s second solo-show with the gallery.

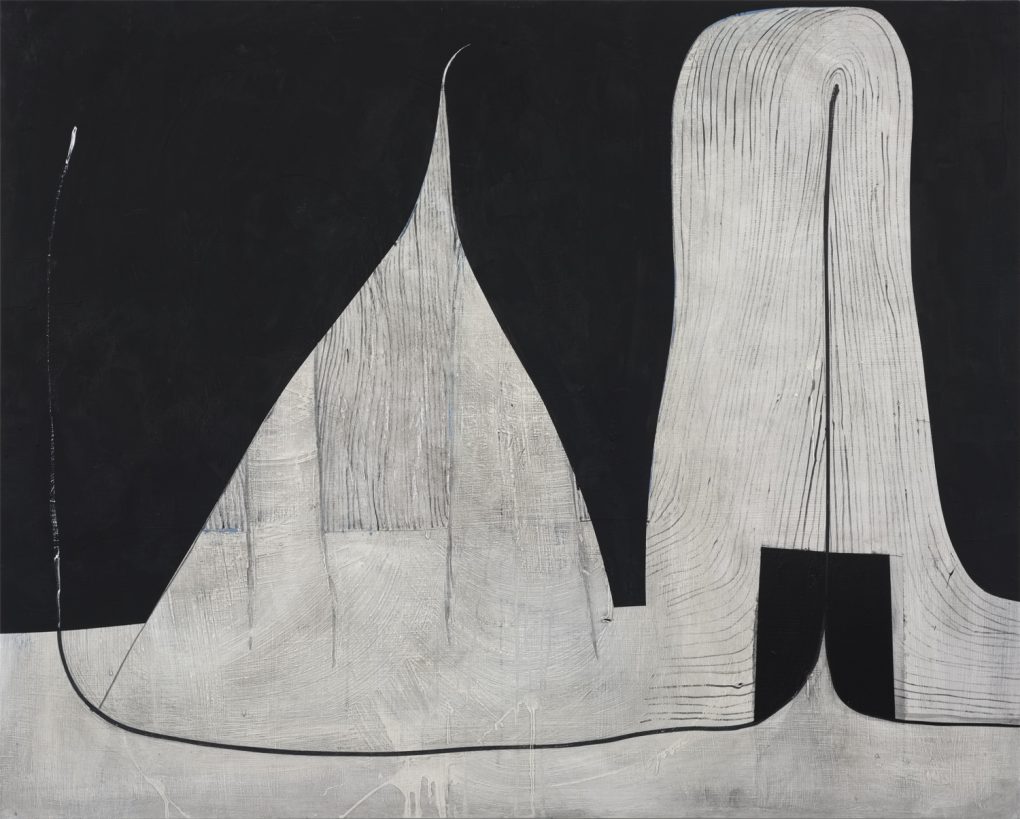

Created from layers of plaster, resin and waxes, Hamada transforms raw materials into sculptures with impressive scale and infinite detail. Taken as a whole, the

volumes he creates vary from simple geometric forms to extremely complicated amalgamations of shaped volumes. However, upon closer inspection, the

surfaces of the sculptures reveal a myriad of individual cells replete with painted and sculpted pattern. This part-to-the-whole relationship is a theme that runs

throughout Hamada’s oeuvre, echoing the artist’s own social consciousness and his interest in the way individual contributions effect larger systems.Executed with incredible restraint, Hamada limits himself to a neutral palette consisting primarily of black and white [and on occasion, more coppery hues].

This, along with the absence of descriptive titles – each piece is sequentially numbered as it is completed – gives the sculpture an austere quality that allows

for the viewer to bring individual significance to the work. Yet this austerity is not a perfect one. It is tinged with a timeworn patina of dented edges and

scratched surfaces, which imbues the work with wabi-sabi, the Japanese aesthetic in which beauty is imperfect, impermanent and incomplete. While this is not

a part of his conscious approach, the artist acknowledges its presence, noting that momentariness is “one of the most fundamental truths we have.”Hamada’s work often presents itself to the viewer in seemingly opposing dualities: archaic and futuristic, natural and industrial, restrained and effusive. Indeed,

the sculptures are as familiar as they are foreign, and yet, it is this Heraclitian relationship that drives the artist’s practice. Deeply conscious of the

omnipresence of social and political issues at large, Hamada explains that within his studio he strives “to find fine balance in elements to see things being

harmonized, opposing elements coexisting in meaningful ways, richness and warmth being born out of raw materials.”Hiroyuki Hamada was born in 1968 in Tokyo, Japan. He moved to the United States at the age of 18. Hamada studied at West Liberty State College, WV before

receiving his MFA from the University of Maryland. Hamada has been included in numerous exhibitions throughout the United States including his previous

exhibition, Hiroyuki Hamada: Two Sculptures, at Lori Bookstein Fine Art. He was the recipient of the New York Foundation for the Arts Grant in 2009 and the

Pollock-Krasner Foundation Grant in 1998. Most recently, Hamada’s work was featured in Tristan Manco’s Raw + Material = Art (Thames & Hudson). The artist

lives and works in East Hampton, NY.Hiroyuki Hamada will be on view from October 10 – November 9, 2013. An opening reception will be held on Thursday, October 10th from 6-8 pm.

Gallery hours are Tuesday through Saturday, 10:30 am to 6:00 pm. A catalog of this exhibition will be available later this fall. For additional information and/or

visual materials, please contact Joseph Bunge at (212) 750-0949 or by email at joseph@loribooksteinfineart.com. -

Adam Stennett’s Artist Survival Shack

Last weekend I took my kids to Adam Stennett‘s art project “Artist Survival Shack” in Bridgehampton, NY. Adam is an artist from Brooklyn. After the market crash of 2008, he had to be away from his art a little concentrating on making ends meet. This project marks his first major project in 5 years.

The past a few years have been a time of contemplation for me as well. To me, artists explore possibilities of how we can be, how we see things and how our world can be. And we depend on our radars high up in the air beyond our social restrictions, authoritative controls, religious guidances, and so on to see our own visions. We reflect the wider reality that’s in synch with the time beyond our civilization, our domestic habitats, and the corporate cage of the mainstream culture. But I feel that I am in the minority among the artists today.

I am not saying that we should all be activists or start doing political art but I find it’s so disturbing, for example, that many of us willingly support politicians who colonize other nations, cut our vital social programs in favor of wars, jail whistleblowers to torture, deceive people to pass pro corporate laws, sell our health for profits, imprison people for cheap prison labor, support political assassinations, detain human rights activists… And there is not enough outrage among us the artists. The ones who are regarded as the finest, the most respected, think nothing of bowing down to the authority, receiving medals of honor from the very culprit of the tragic decisions.

So when Adam told me about his self-sustaining off-the-grid survival shack for making his art. I immediately understood his intention. To me it is an experiment in detaching the artist from the machine. He collects rain water to bath, to cook and to water his vegetable plants. He gets electricity from the solar panel. He composts everything including his waste to fertilize his plants and to experiment with the native plant growth.

When he showed me his spud gun and a bow and arrows in his shack, I knew that he was poking fun at our helplessness and desperation against the overwhelming capability of the machine to kill and destroy.

And when he showed me a piece made with golf balls with corporate logos–Dow chemical, Lockheed Martin, Monsanto, Raytheon, Boeing, Northrop Grumman, GE and etc.–and government agency insignias, I was struck with an image in my head of the players of the deep state discussing the future of the machine.

So in short, it was really nice encountering another soul struggling to make sense out of our time: Struggling to show us our potential as artists in the sea of the corporate world.

Also, having my kids around made me realize that his shack is his “fort”. It’s a little safe place with everything he needs. No one interferes. His world is there as he dreams. It’s so great to be an artist.

Adam will have a solo exhibit showcasing the results of his month long self-sustaining survival project at Glenn Horowitz Bookseller, East Hamton Gallery, opening on 9/7/13. There will be his actual shack with the solar electric equipment, composting kit, painting studio set up, and of course his paintings done during his stay in the shack.

His outdoor shower set up. The black tank on the right is heated by the sun and manually

pumped for bathing.

His vegetable garden is enriched by the special survival shack fertilizer (a mixture of one part pee and 5 parts water).

Interior of the Artist Survival Shack

Cosmo Hamada trying the bow and arrow

The golf ball piece in progress. The shack is located on a private land by a golf course for the wealthy.